Spoken-word poet Emily Joy went viral on Twitter in 2016 with her powerful video “How to Love the Sinner & Hate the Sin: 5 Easy Steps”, a satire that indicts the heartlessness of anti-LGBTQ Christians using their own catchphrases. “Religious freedom means never having to say you’re sorry/ You can love people and take away their rights.” She’s also been a prominent critic of sexism and victim-blaming in Christian purity culture.

For my Lenten discipline this year, I wrote in the journaling workbook she created, Everything Must Burn: A Spiritual Guide to Starting Over. Designed for survivors of fundamentalism and spiritual trauma, the simple 8-week program covers topics such as Sexuality, Shame, Hell, and Creativity, with brief questions that prompt us to articulate our old and new beliefs, and affirmations of God’s inclusive love. Here are a few of my musings, lightly edited for clarity:

What do you believe about the nature of God?

I often believe that God is unknowable and too tremendous for our consciousness to interact with without exploding. (Very Lovecraftian!) When I try to live into the hope that God is a goodness and love that wins out over cruelty and entropy, the closest I can get to awareness of that God is…the “deep and dazzling darkness” of Henry Vaughan’s poem.

…I’m not ready for God’s heartbreaking love. To feel the grief of not being loved that way for all of my youth.

…I’m going to try to be less fearful of God by identifying “God” with the magic-filled universe.

What is the place of anger in your spiritual and creative life?

In my creative life, anger is often the dynamite that knocks down the writer’s block of self-doubt and shame. That Anaïs Nin quote about staying in the bud being more painful than blossoming–for me it’s like, the time comes when my hair is too much on fire to give a flying fuck what anyone thinks of me.

…I’m angry that I no longer trust spiritual teachers and religious institutions because I feel they’re trying to sell me something–the belief that their system or community is complete and necessary for my well-being. At bottom, they all want me to feel unable to live without them and guilty of disloyalty for drawing on other support systems–just as my mother did! Am I just triggered? No, I am genuinely angry at hegemony as a human impulse.

…I feel really sad when I reflect on all of this. I sense in myself a deep need to be seen, consoled, and vindicated (Psalm 17). In the olden days, I’d say “God is the one to meet that need”, but now I react with suspicion to that facile doctrine–it’s a handy excuse for other people to avoid mutuality in relating to me–or for me to despair of asking for support from anyone outside my own head. And I guess I’m angry that there’s no venue or vocabulary in mainstream church culture or progressive theology to even address this as an issue.

Do you believe that God is the sort of being to send creatures they love to hell? What were some of the messages you received about hell growing up?

I’m lucky that I was never raised with the concept of salvation/damnation dependent on what religion you believed in… I didn’t need any worse concept of hell than being seen for my true self and deemed unworthy of love. Hell was being cast out from the presence of love, inescapably confronted with the truth of my loathsomeness forever.

I didn’t pick up this primal dread from Christianity, but Christianity found a hole in me for this fear to root in. I was vulnerable to this shitty theology that grace is merely a legal fiction (simul justus et peccator) whereby God pretends not to notice how awful you are.

That’s not love, but Christianity manipulates you into thinking you have to settle for it–then blames you for not feeling loved or loving God back. Negging as evangelism!

…I think that hellfire theology motivates you to see the worst in people because you know deep down how unfair it is–so you have to look for reasons why every sin is a bigger deal than it really is.

Do you see a difference between shame and guilt? Do you think God wants you to feel shame?

Can we distinguish, more than “grace alone” Protestants do, between shame and guilt? Grace sets us free from shame by telling us that our essence isn’t repulsive and nothing can separate us from God’s love. But if we say it also sets us free from guilt, we shirk the responsibility to make amends and take our sins seriously. I don’t think God wants us to feel shame, because shame is so intolerable for the ego that it takes away the base of safety that we need to change our ways.

…My faith, as I once knew it, can’t recover from the realization that my shame was the product of abuse, not genuine depravity. Protestantism will never let people actually live in the grace that it promises, because of its false claim that we are right to be ashamed–that self-loathing is factually based in unspeakable guilt, instead of being an illusion from imperfect parental attachment.

What do you believe love is?

Two things I have a problem with in how “love” is deployed in Christianity: (1) “Love” as an excuse to say coercive, scary, erasing things to people “for their own good”; (2) “love” as obligatory toward, or more praiseworthy when directed toward, people who intend harm to us.

Today I took a walk on the bike trail to enjoy the spring sunshine. I admired a young woman’s cute little dog. The woman, with a teary joyfulness, told me she takes every opportunity to talk to people about her near-death experience and how Jesus cured her cancer, because she now knows Jesus is the only way, and she’s worried I won’t make it to heaven. I thanked her pleasantly and noncommittally, and walked away feeling sad, breathless, homesick for a kind of peaceful certainty I’ve never had. What is God’s love, really? It’s the shameless innocence of the dog running through the woods, oblivious to the fearful system his mistress has embraced to solve a self-created problem.

…Now I feel like taking a page from this woman’s book and commemorating Transgender Day of Visibility by standing on a street corner and asking people if they’ve read the Good Word of Judith Butler. “I just want everyone to know that gender is socially constructed! The truth will set you free!”

…It’s so fucking hard to love one’s friends and family properly, I’ve got no time for hugging neo-Nazis! Cynical aside: perhaps for some people it’s easier to “love” an enemy because there’s no feedback mechanism. It can all be a self-flattering illusion. Your enemy can’t call you out, like a real friend does, because you’ve already decided to ignore their opinion of you.

What does it look like to live creatively?

To live creatively is to trust myself to follow my instincts into unknown territory. To pursue what excites me (or take a rest when I need it) without having to know how it turns out or explain why this is what I’m doing.

I fear that “creativity” gets confused with “productivity” such that my self-image as a creator must be constantly proven with output. Or that creativity becomes a burden, like the “devotion” my mother supposedly gave me–a privilege that can never be repaid, a duty to prove that I’m grateful all the time and not squandering my potential.

…I try to follow Elizabeth Gilbert’s advice in Big Magic that I should revel in the freedom of my unimportance, but that doesn’t work well for a naturally depressed person. I am still searching for what it would mean for my work to “matter”–what’s a healthy, non-egotistical, inner-directed way for that need to be met? I sense that as long as I look to someone else for that validation, I’ll live in fear–even if the someone else is God, because a good parent God would not base their love on my achievements. What would make my work matter TO ME?

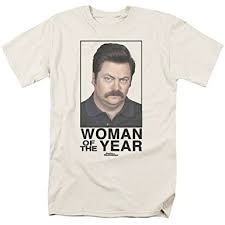

Jack Gilbert (no relation) had it right–go live on a fucking island with your goats and your three wives and let your friends drag you out to publish a book every 10 years. He was like the Ron Swanson of poetry.

…I’m starting to develop evidence-based faith that I can manifest changes in my life that I once despaired of. And that is creativity–thinking outside the limits of what the literal mind takes to be impossible… Being trans is one of the most creative and magical things I’ve done. I’m willing a new gender into existence.