The girly pink explosion of sweetness that is Mother’s Day will soon be upon me again. Do I have a problem with that?

I love this little guy, and I love pink.

But when I think about being a mother, the images that come to mind are not sugary, soft, and girly. I channel the power of a mother tiger protecting her cub. I am a warrior, proud of my battle scars. I feel some kinship with the Hindu goddess Kali, who is one of the incarnations of Mother Durga, creator and destroyer of all things. In Sanskrit, “Durga” means fortress. As a mother, I hold psychic boundaries around my home to make a sacred space where my child can grow safely.

I want to celebrate motherhood in a way that doesn’t erase the difficulties of embracing femininity under patriarchy. I want space to grieve the brokenness of my memories of my own mother. In time, Shane may have complicated feelings about Mother’s Day, too, because it encompasses his birthmother’s loss as well as my gain.

If, for whatever reason, you’d like to add some emotional nuance to your observance (or boycotting) of this holiday, the readings below may be of interest.

At the excellent blog Women in Theology, Janice Rees reviews a documentary about a teenage daughter and her mother’s gender transition to male:

The film’s questions around trans identity helps us to push the motherhood category, or rather, to see it in its normative form. That is, for bodies with wombs that have borne children, an alleged and drastic ontological shift is enacted, and a new normative way of being embodied is established.[3] No longer women (which continues to be the norm for wombed childless bodies), these bodies, from all accounts, take on a new status as ‘mother’. To be a mother is to be caught up in this new quasi-subjectivity. I write this as a parent, one who almost always hesitates on this capital M word, this form that overwhelms me with its situated concreteness. Now, having endured the kind of discrimination and expectations placed on mothers, I find it hard to see a future in motherhood, or any sense in its usefulness as a term…

…Ultimately, this fixed category of mother becomes a foundational lens in which we not only read the quasi-subject (who is mother) but through which other, childless subjects, may emerge in more fluid identities. That [the daughter] Billie’s story becomes the primary lens in 52 Tuesdays is hardly surprising…yet James continues to subvert his status of mother – not due to the supposedly obvious implications of transgender transition, but because of his trans-formation back into a person who wants to be someone. And if having a womb and or being a parent has a future – at least for those of us who feel marginalised and oppressed by the normative categories of gender, and this peculiar ‘mother’ status – then there is something profoundly liberating in James’ subversion…

****

Dr. Karyl McBride, author of Will I Ever Be Good Enough? Healing the Daughters of Narcissistic Mothers, writes on the Psychology Today blog about the painful double standard that this holiday can bring up:

Mother’s Day is approaching and this time of year discussions about mothers explode, but of course the roaring voices describing maternal narcissism are hushed to the background. We hear the praise and celebrations about good mothering, but simultaneously the complete stillness and silence about inadequate mothering…

…If adult children of narcissistic parents discuss their upbringing, they are usually met with disdain. “Good girls or boys don’t hate their mothers!” “There must be something wrong with you, if you are not connected with your mother.” “It must be your fault.” So, this population of people goes into hiding. They go back to what they were taught and practice superficial pretending which does not help their own recovery process. They are told once again to “put a smile on that pretty little face and pretend that everything is just fine with this family.”

But here’s the misnomer. If a narcissistic parent raised a daughter or son, it means that the parent was not capable of empathy and unconditional love. So, that child did not receive the bonding, attachment and maternal closeness from that parent. The issue lies in the disorder of the parent. It does not mean that the daughter or son is not capable of loving or that they don’t love that parent. In fact, these adult children have spent their entire lifetimes trying to get attention, love, approval, and nurturing from the narcissistic parent to no avail. What I have seen in my research and work is that adult children who come from narcissistic families dearly love their parents and the issue is that the parent is not capable of loving them back. Therein lies the need for acceptance and grief for the adult child and this is the first step in their recovery process. But, because the adult child is reacting to the lack of maternal love, they are seen as the one who does not love the parent. This misnomer is not readily understood…

…So let me ask you this: Because you see the disorder in the parent and you are reacting to it and working your own recovery, do you think that means you don’t love your parent? Or are you simply standing in your truth, accepting your reality, and working on your own mental health?…

****

Finally, let’s remember that before Mother’s Day became a showcase for perfect performance of gender roles, it was a rallying point for women’s activism, as Christian scholar Diana Butler Bass explains in this HuffPo article, “The Radical History of Mother’s Day“:

..In May 1907, Anna Jarvis, a member of a Methodist congregation in Grafton, West Virginia, passed out 500 white carnations in church to commemorate the life of her mother. One year later, the same Methodist church created a special service to honor mothers. Many progressive and liberal Christian organizations — like the YMCA and the World Sunday School Association — picked up the cause and lobbied Congress to make Mother’s Day a national holiday. And, in 1914, Democratic President Woodrow Wilson made it official and signed Mother’s Day into law. Thus began the modern celebration of Mother’s Day in the United States.

For some years, radical Protestant women had been agitating for a national Mother’s Day hoping that it would further a progressive political agenda that favored issues related to women’s lives. In the late 19th century, Julia Ward Howe (better know for the “Battle Hymn of the Republic”) expressed this hope in her 1870 prose-poem, “A Mother’s Day Proclamation” calling women to pacifism and political resistance…

Years later, Anna Jarvis intended the new holiday to honor all mothers beginning with her own — Anna Reeves Jarvis, who had died in 1905. Although now largely forgotten, Anna Reeves Jarvis was a social activist and community organizer who shared the political views of other progressive women like Julia Ward Howe.

In 1858, Anna Reeves Jarvis organized poor women in Virginia into “Mothers’ Work Day Clubs” to raise the issue of clean water and sanitation in relation to the lives of women and children. She also worked for universal access to medicine for the poor. Reeves Jarvis was also a pacifist who served both sides in the Civil War by working for camp sanitation and medical care for soldiers of the North and the South.

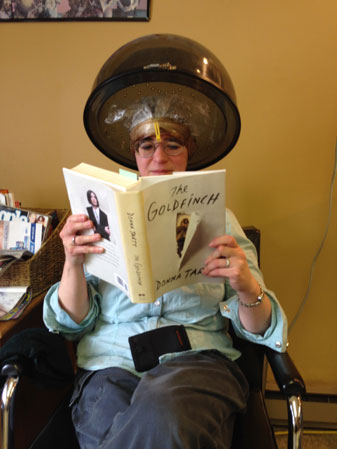

My awesome mom-of-choice, Roberta, marching with OLOC at Northampton Gay Pride 2014.