July 2009…

…November 2019.

Greetings, loyal readers! It’s been a decade to remember. As my 30s segued into my 40s, I changed my gender, pronouns, religion, and pants size; fired my abusive mother; adopted Lord Bunbury, the cutest boy to ever eat a quarter-pound of lox in one bite; and published five books of sad poetry and smutty fiction.

Julian says, “You just get better with age, darling.”

Biggest Decision of 2019: Starting HRT.

Since October I’ve been taking low-dose testosterone in gel form. (I know, I know, real men shouldn’t be afraid of needles…) Not much visible change yet, but I feel very handsome and full of creative ideas.

Speaking only for myself here–you don’t have to do anything medical to be a “real trans”!–bringing my subjective sense of masculinity into objective physical reality via HRT has felt like an act of magical manifestation. I grew up in a home dominated by gaslighting. Maintaining my inner truth against constant assaults was exhausting. Being trans sometimes feels that way too. If my womanhood falls in the forest but everyone still calls me “Ma’am,” does it make a sound? My little bottle of Love Potion Number 9 gel is something I can point to, a fact in the world, a self-affirming decision to be myself outwardly and not only in my fantasy life. It tells my younger psychological parts that we’re finally safe to come out of the closet (and give away those uncomfortable high heels).

Happiness Comes in a Pill: For the first time in my life as a congenitally anxious person, I’m also taking Effexor, a mild anti-anxiety drug. The main benefit is that I sleep more deeply and have vivid dreams that seem meaningful at the time. For instance, a couple of weeks ago I dreamed I was re-creating the Bloomsbury Group out of Lego. Thanks a lot, Carolyn Heilbrun.

Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington, and Virginia Woolf.

I Wrote Some Stuff: I participated in the Center for New Americans’ 30 Poems in November fundraiser again this year, writing more strange poetry for a new chapbook. It’s not too late to contribute to this great organization that provides literacy instruction, job training, and naturalization assistance for immigrants in Western Massachusetts. Visit my sponsorship page here.

In addition, my poem “psalm 55:21” won the local category of the 2019 Broadside Award and Glass Prize from Slate Roof Press. The award was $250 and publication as a limited-edition broadside. You can read the winners on their website.

Young Master Update: His Nibs earned an orange belt in Tae Kwon Do this year, switched his allegiance from Pokémon to Minecraft, and learned to read chapter books on his own. (Shout-out to the “Captain Underpants” book series for making one of its main characters gay in the last installment.)

Fractions, Mommy!

We undertook a perilous trip by plane (me) and car (Daddy and Shane) in an April snowstorm to visit Shane’s birth mother in Wisconsin, where she was hospitalized for liver failure. Sadly, Stephanie passed away this August at age 45. She lives on in his happy-go-lucky personality, mechanical skills, and love for the arts and animals.

Stef and the Bun in October 2012.

Highlights Reel: With some trepidation, I have combed the Reiter’s Block archives for posts from the past decade that I still agree with. Sometimes I’m embarrassed by how passionately (and dickishly) I defended beliefs that let me down in the end. But as Julian would say, you can only wear the clothes you have. Some people grow up by learning from failed love affairs. My method was to throw myself fully into the best available worldview at the moment, searching for an ethical foundation and a compassionate space where I could discover myself. What if I’d known about FTM transition in 1983, or demisexuality in 1997, or trauma theory in 2006? Well…I didn’t. Here’s what I did instead.

2009: I was really preoccupied with how to be a Bible-believing yet gay-affirming Christian, because I still had faith that good theological arguments would make a difference. Sigh. If this is your jam, check out the posts “Writing the Truths of GLBT Lives” and “Liberal Autonomy or Christian Liberty”. Also, my most ambitiously insane chapbook, Swallow, was published by Amsterdam Press. Now out of print; email me for a copy.

2010: More gay Christian angst. I noticed the questionable respectability politics of some gay-affirming theology in “The Biblical Problem of the Prostitute”. Seriously starting to wonder why writing as fictional “Julian” felt autobiographical: “Straight Women, Gay Romance”. Marched in Northampton Trans Pride as an ally. Didn’t blog much that year because secretly coping with failed-adoption trauma and abusive mom meltdown. Another chapbook published: read the title poem in the post “‘Barbie at 50’ Wins Cervena Barva Poetry Prize”. Also received Massachusetts Cultural Council fellowship in poetry. Misery has never stopped me from being productive.

2011: I went no-contact with my mother, and shortly thereafter, mom-of-choice Roberta left her as well. I was still under the social workers’ microscope in the adoption process so I barely posted anything about my personal life on the blog. In September, Stef contacted us through our adoption website, and the rest is history. The series “Letter to an Evangelical Friend, Part 1: Why I Don’t Read Anti-Gay Theology” and “Part 2: Obeying Jesus Without Knowing Him?” is the culmination of 5 years wrestling with the gay Christian issue, and in retrospect, already shows the de-conversion that I would take several more years to admit to myself and others. I also gave myself this advice on my 39th birthday: “Every five years, you will completely change your mind about something important, so don’t be a butthole to people who disagree with you now.”

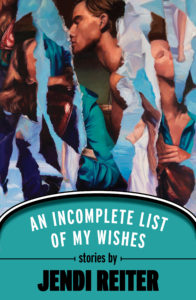

2012: Welcome, Bun!! I blogged about why “Adoptive Families Are Queer Families”. In other news, the title story of my eventual debut collection An Incomplete List of My Wishes won an award from Bayou Magazine. I read Judith Herman’s Trauma and Recovery. I turned 40 and wrote a three-part roundup of the books that influenced my youth.

2013: Is it gender dysphoria or is it sexism? Less filling, tastes great! I battled cultural expectations of femininity and motherhood in “The Gorgon’s Head: Mothers and ‘Selfishness'”. (Thanks to Bun for sleeping through the night at 6 months old, so I had the energy to string sentences together.) I self-identified publicly as a child abuse survivor for the first time in “National Child Abuse Prevention Month: Why It’s Personal”. In “Imitation of Christ, or Substitute Savior?” I questioned whether it’s possible to write a “Christian” novel without romanticizing codependence. In “Framing Suffering: Survivors, Victims, and Martyrs”, I began asking the church to consider liberation theology from an abuse-survivor standpoint–a project I’d ultimately drop after recognizing its basic incompatibility with mainstream Christianity.

2014: I dyed my hair red. Many boxes of books were given away, with “Thoughts from the Great Book Purge of 2014” surveying how my beliefs had changed. I wrote a series on Survivors in Church: “Between Covenant and Choice”, “Our Spiritual Gifts”, and “Insights From Disability Theology”. But it became evident that I had to leave church altogether: see “The Priesthood of All Survivors”. After 6 turbulent years, I finally finished an acceptable draft of the Endless Novel a/k/a Two Natures. To celebrate, I got a tattoo.

2015: I began studying Tarot, as described in “The Spiritual Gift Shop: Or, Living in Syncretism”. My second full-length poetry collection, Bullies in Love, was published by Little Red Tree. In “The Hierophant or the Ink Blot Test”, I explored where accountability can be found in a self-directed spiritual practice. I met Elisabeth Moss, who played my favorite character on “Mad Men”! The Supreme Court ruled that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marriage equality. I won $1,000 from Wag’s Revue for a poem about buying a plastic dick. (No wonder that was their last issue.)

2016: Two Natures was published by Saddle Road Press! I blogged about why I write explicit sex in my fiction (“Sex God”), and the pros and cons of the radical feminist critique of Christianity (“Christianity, Patriarchy, and Abuse: Cross Purposes”). I tentatively came out as genderqueer in “Nonbinary Femme Thoughts”. My story “Taking Down the Pear Tree”, a semi-autobiographical tale of painful setbacks on the road to adoptive parenthood, won the New Letters Prize for Fiction. However, the year ended badly for the planet with the election of Tan Dumplord.

2017: Our storage unit raised their prices, so we let the lease expire and brought back a truckload of memorabilia to Reiter’s Block HQ. Some of my archeological finds are described in “Killing You in My Mind: My Early Notebooks”. I self-diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum. The Aspie community’s acceptance of finding emotional qualities in “inanimate” objects (“Autistic Pride Day: Everything is Alive”) paved the way for me to study Magick. I took charge of the Young Master’s religious education with a family trip to NecronomiCon Providence (“The Cthulhu Prayer Breakfast and the Death of White Jesus”). I killed off my menstrual cycle with the Mirena IUD, ending three decades of disabling chronic pain from endometriosis (and, as it turned out, gender dysphoria). Our high school had a collective reckoning with the #MeToo Movement on our alumni Facebook page.

2018: My debut story collection An Incomplete List of My Wishes was published by Sunshot Press, an imprint of the journal New Millennium Writings. Adam and I celebrated our 20th wedding anniversary. I took an online course from anti-racist group White Awake about decolonizing our New Age spirituality (“Problems of Lineage and Magic”). Christian feminist author Emily Joy’s Lenten journaling workbook Everything Must Burn helped me process my spiritual trauma. I regret that I didn’t write to Dr. James Cone before he passed away, because our church small group was passionately inspired and challenged by his book Black Theology and Black Power. (I was embarrassed to imagine that he’d say, “Well, light dawns over Marblehead, white ladies!” Centering my own feelings like a typical whitey…) For the same class, I did a 40-day Bible journal (“Daily Bible Study Is My Problematic Fave”) and tried not to laugh at evangelical prayers like “invade me with your burning fire”. (Okay, I didn’t really try.) But it helped me get through losing one of my best friends. “Drawn That Way: Finding Queer Community at Flame Con” recounts my trip to an LGBTQ comics convention for research on the Endless Sequel.

2019: I did another purge of books and clothes that didn’t spark genderqueer pagan joy (“Facing Literary Impermanence with Marie Kondo”). As more research for the Endless Sequel, and let’s face it, to buy gay erotica, I attended Queers & Comics at the School of Visual Arts (“Mama Tits, Pregnant Butch, and More”). I considered the symbolic appeal of Satan and Cthulhu for spiritual-abuse survivors in “Two Varieties of Post-Christian Experience”.

In the year ahead, I hope we can elect a Democratic president and reverse course on the imminent destruction of democracy and the planet. Beyond that, my goals are the same as before: Be more trans, do more magic, lift more weights, write more words! Thanks for traveling with me.