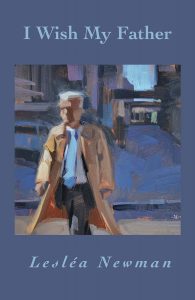

Shepherding an elderly parent through illness and death is a stark, unglamorous journey that demands clear vision and directness, and (especially if you’re a Jewish New Yorker) a fair amount of gallows humor. These qualities abound in Lesléa Newman’s latest poetry collection, I Wish My Father (Headmistress Press, 2021).

Dedicated to Edward Newman (1927-2017), a dapper and hardworking New York attorney, this sequence of narrative poems cycles repeatedly through grief, frustration, and absurd humor, as his adult daughter endeavors to preserve his dignity and safety (not always compatible goals) while his grasp of reality weakens. There’s a certain kind of Jewish couple for whom bickering is a love language. One gets the sense that Newman’s late parents often communicated in this register, which makes her widowed father’s moments of romantic sorrow all the more poignant.

The collection is unified not only by the storyline but also by a formal similarity among the poems. Each poem’s title serves as the first phrase of a sentence that continues as a sequence of three-line stanzas. This device, never obtrusive, reinforces the feeling of sameness that must have burdened her father’s days once his mainstays of work and marriage were torn away. And yet there is change, painfully perceptible to his daughter if not to him.

…He looks towards

my mother’s chair, and out of nowhere

I hear her, too, her voice the weak whisper

of that terrible last day. Don’t worry,

sweetheart. She cupped my cheek

with her worn, withered hand.

There’s no problem so terrible

that it can’t get worse.

Now, that puts the “dead” in deadpan humor. Look how deftly the anecdote is saved from sentimentality by an unpredictable bit of very Jewish wisdom that is both optimistic and so pessimistic we can hardly stand it. As Leonard Cohen sang, You want it darker…

Faith is more than a cultural style here, though. Mr. Newman seems largely contented by his delusions–or are they visions?–of mysterious children at his bedside and random dead people from his past. Together they observe Yom Kippur in a nontraditional way that still brings his daughter closer to the mysteries of time, repentance, and forgiveness. And when he is released from his earthly life, she narrates his arrival at her mother’s side in the World to Come, in exactly the same factual voice as the preceding poems.

I appreciate how this book is accessible to readers without a background in poetry, while also revealing depths to an experienced writer and reader. Even the Young Master took an interest when he saw the book cover, asking me “What does that mean? I wish my father what?” I read him the title poem, about Lesléa’s father tallying the events of his life at age 90, and then asked Shane, “What do you think she wishes for her father?” His suggestions:

I wish my father was still alive.

I wish my father had a good life.

I wish my father knows he was the best.

Click the cover image to be taken to the book purchasing website. Lesléa has kindly permitted me to reprint the poem below.

MY FATHER WAS NEVER

on time once in his entire life.

No, we could always count

on him being a good 20 minutes

early. I remember many a Saturday

night with my dad dressed

to the nines in his sleek black tux

and glittering diamond studs

pacing the hallway from front

door to kitchen to dining room

before ordering me to dash

upstairs and see what was taking

my impossible mother so goddamn

long. I’d find her sitting side saddle

on a stool in a white silk slip

surrounded by crumpled tissues

imprinted with lip prints

of lipstck the color of apples,

clasping a sparkling bracelet

around her wrist, clipping

on a pair of matching earrings

and muttering to herself in the bedroom

mirror. “I know the early bird catches

the worm. But who the hell

wants a goddamn worm?” She’d hand

me a pendant shaped like a tear

to fasten around her neck,

then raise a silver aerosol can

the hairspray hissing like a snake

as she circled her head three times

forcing me to step back from the cloud

that always made me cough. Once

I came home from college

for Thanksgiving and my dad

drove me to the airport for my return

flight on a snowy Sunday afternoon.

Somehow my stuffed-to-the-gills suitcase

never made it out to the car.

After a ton of yelling and screaming

and carrying on, my father drove

us home and drove us back

to the airport and I was still

an hour early for my flight.

It made me laugh when my father

proudly showed me a note

he received after my mother died:

Dear Mr. Newman,

Thank you for coming to my Bar Mitzvah.

You were the first one there.

I wonder just how early he was

and how on earth he would feel

to learn that from this day forth

for all time he will always

and forever be known

as the late Mr. Newman.

© 2021 Lesléa Newman from I Wish My Father (Headmistress Press, Sequim, WA). Used by permission of the author.