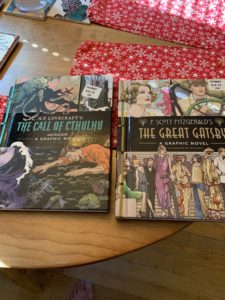

You just never know what you’ll find at Adam’s favorite superstore. I suppose Lovecraft’s Black Goat of the Woods with a Thousand Young needs those jumbo-sized cans of tomato sauce to feed all the kids.

A bit late with the link-o-rama this month because I’ve begun Year Two of the Temple of Witchcraft Mystery School. This year I’ll be learning spell-crafting, altar-building, how not to kill my houseplants, and possibly an answer to the question “Is it cheating on your marriage to have sex with a god?”

Talented essayist Grace LeClair, a fellow regular in the Tarot writing workshops I’ve attended since 2015, pushed the boundaries of 1960s propriety when she challenged Barnard College’s outdated rules against cohabitation and its curfews for female students. The Columbia Spectator interviewed her recently about her undergraduate activism, which made her a target of the tabloids in New York City. The all-women’s college folded on its feminist principles because of pushback from wealthy pearl-clutching alumnae. Grace, then known as Linda, courageously stuck to her message that her campaign was not about sexual license but empowerment and equality–the very reasons she’d chosen a women’s college in the first place.

A less sympathetic tale of activism comes to us from–where else?–Texas. NBC News and ProPublica reported last month on a contentious school board meeting in the North Texas town of Granbury:

For months, the woman in the clip had been demanding that the Granbury Independent School District ban from its libraries dozens of books that contained descriptions of sex or LGBTQ themes — books that she believed could be damaging to the hearts and minds of students. Unsatisfied after a district committee that she served on voted to remove only a handful of titles, the woman filed a police report in May accusing school employees of providing pornography to children, triggering a criminal investigation by Hood County.

Now, in the video that Weston found online, she was telling the school board that a local Christian pastor, rather than librarians, should decide which books should be allowed on public school shelves. “He would never steer you wrong,” she said.

The clip ended with the woman striding away from the lectern, and the audience showering her with applause.

Weston, 28, said his heart was racing as he watched and rewatched the video — and not only because he opposes censorship. He’d instantly recognized the speaker.

It was his mother, Monica Brown.

The same woman, he said, who’d removed pages from science books when he was a child to keep him and his siblings from seeing illustrations of male and female anatomy. The woman who’d always warned that reading the wrong books or watching the wrong movies could open the door to sinful temptation. And the one, he said, who’d effectively cut him off from his family four years ago after he came out as gay.

I love erasure poetry because it flips censorship on its head. Words and lines are blocked out, not so much to silence the source text, but to make it speak a hidden message, or to talk back to its oppressive assumptions. When he was in prison, my pen pal “Conway” used to make powerful erasures out of disciplinary memos. Poet Jennifer K. Sweeney has a series of such “effacements” posted in the online journal Gasher, using collage and erasure to break open the constraints of a 1950s etiquette manual.

An insightful New York Times video series by James Robinson about living with disability profiled Paul Kram, who has prosopagnosia (face-blindness). As someone with a less severe version of this condition, I found his experience relatable. At one point the video shows faces turned upside-down, making them harder to recognize. This disorganization of data is similar to how facial information enters a face-blind person’s brain. Along those lines, I had a dream the other night where someone got my pronouns wrong, and I replied, “It’s okay, I can’t recognize people I already know, so I can see how certain things just don’t stick in your mind, either!”

Slippery identities and slanted stories are the theme of Kij Johnson’s “Five Sphinxes and 56 Answers” in the latest issue of the experimental lit mag DIAGRAM. The award-winning fantasy writer braids a Midwestern girl’s coming-of-age story with variations on the Oedipus myth, exploring the intergenerational misunderstandings and enforced silences of women throughout the ages.

You have come to accept that she is who she is because of her own confusing and critical mother, and the cycle goes back through forever it seems: women unhinging their pelvises to bear other women and then getting started on the hard work of dying, back and back and back, mothers and daughters and mothers of monsters.

Mixed messages, riddles you can’t solve. You stand at the entrance to a great city, the world. Your mother waits astride the rock that bars your way. The first riddle ends in your adulthood; it is unlikely she will be alive for you in your three-legged stage, though perhaps she is counting on you being there for hers.

The second riddle is existential, and there is no answer. Night and Day. Living ’til night or waking up in the morning is always a matter of faith. In the end, both women die.

Your mother is also Hera, angry and vengeful and punishing the wrong people.

You mother is also what you have tried hard not to grow up to be. Have you succeeded? Could she have done better? Have you?

There are other versions of this story, as well.

Also in DIAGRAM, Tyler Raso’s “Personality Index” cleverly reads as both a numerical questionnaire and, if you ignore the numbered part, a poem composed of the phrases in the left column. I do love me some psych-test satire.

Sanah Ahsan’s column in The Guardian, “I’m a psychologist–and I believe we’ve been told devastating lies about mental health,” unpacks why I often find psych checklists reductionist and insulting.

If a plant were wilting we wouldn’t diagnose it with “wilting-plant-syndrome” – we would change its conditions. Yet when humans are suffering under unliveable conditions, we’re told something is wrong with us, and expected to keep pushing through. To keep working and producing, without acknowledging our hurt.

In efforts to destigmatise mental distress, “mental illness” is framed as an “illness like any other” – rooted in supposedly flawed brain chemistry. In reality, recent research concluded that depression is not caused by a chemical imbalance of the brain. Ironically, suggesting we have a broken brain for life increases stigma and disempowerment. What’s most devastating about this myth is that the problem and the solution are positioned in the person, distracting us from the environments that cause our distress.

Individual therapy is brilliant for lots of people, and antidepressants can help some people cope. But I worry that a purely medicalised, individualised understanding of mental health puts plasters over big gaping wounds, without addressing the source of violence. They encourage us to adapt to systems, thereby protecting the status quo.

Da’Shaun L. Harrison’s book Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness (North Atlantic Books, 2021), which I’m currently reading, makes a similar point with respect to body-positivity. When standards of beauty and health are deliberately constructed to exclude your type of body and subjugate your type of person, you can’t self-esteem your way out of the material disadvantages this creates. More thoughts to come once I’ve finished this radical, brilliant book.

Over at The Philosopher, Olúfémi O. Táíwò’s piece “Being-in-the-Room Privilege: Elite Capture and Epistemic Deference” critiques the simplistic deployment of “standpoint epistemology” to turn the minority member of an elite group into a spokesperson for even less privileged people in his demographic. For instance, the Black professor probably knows more about racial discrimination than his white colleagues, but the factors he has in common with them, such as social class and education, may outweigh the differences. But these spaces tend to operate as though handing the Black professor the microphone is the beginning and end of incorporating truly diverse perspectives. Meanwhile, they don’t notice the other ways their group is homogeneous and unrepresentative.

From a societal standpoint, the “most affected” by the social injustices we associate with politically important identities like gender, class, race, and nationality are disproportionately likely to be incarcerated, underemployed, or part of the 44 percent of the world’s population without internet access – and thus both left out of the rooms of power and largely ignored by the people in the rooms of power. Individuals who make it past the various social selection pressures that filter out those social identities associated with these negative outcomes are most likely to be in the room. That is, they are most likely to be in the room precisely because of ways in which they are systematically different from (and thus potentially unrepresentative of) the very people they are then asked to represent in the room.

This “being-in-the-room” privilege, relative to other members of his demographic, doesn’t discount all the ways that this Black professor may also be disrespected within the room. Standpoint epistemology–deferring to marginalized people as experts on their own experience–can be a corrective “morally consequential practice…of giving attention and respect.” It’s just not the only thing we need to do. Otherwise you get the all-too-familiar political echo chamber of liberal academia, where arguments over symbolic deference take up way more energy than constructive material change. We need to build coalitions across our different kinds of vulnerability, rather than compete for attention by comparing our traumas, he concludes.

I honestly think there’d be a lot more support for affirmative action, reparations, etc. if we took these suggestions and moved away from an attention-scarcity economy.

Finally, enjoy some groundbreaking African photography in this 2020 article from The Guardian, profiling Ekow Eshun’s Africa State of Mind. Adam and I enjoyed seeing queer South African photographer Zanele Muholi’s striking black-and-white self-portraits at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum this past February.