Ash Wednesday selfie with Buddha outside Namaste Bookshop, NYC.

I spent four days in New York City last week to take Internal Landscapes movement lessons with one of my artistic mentors, the choreographer John Ollom. John’s work invites one to occupy the “liminal space” where mental preconceptions are relinquished and new insights arise from listening to one’s body. He challenges the compartmentalization of sacred and profane, regarding Eros as the undivided source from which flows not only sex but spirituality, art, and interpersonal intimacy.

My visit coincided with Ash Wednesday, the beginning of the Christian season of Lent, when we are encouraged to re-evaluate our lives and renounce obstacles in our journey toward God. Lent can be a time when we shame ourselves and further split off the shadow side of our psyche. Or it can be a hopeful movement into the liminal space where we have to trust God more than our ideas about God.

This year, I’m giving up doubting my intuition for Lent.

How do I know when the cadence of a poetic line rings true? What’s that feeling when my novel characters are telling the truth and surprising me, and how’s it different from the gut-level suspicion that we’re bullshitting each other? How does my body, never trained in dance, free-associate from one gesture to the next during an Internal Landscapes lesson, suggesting new images rather than merely illustrating my pre-conceived storyline? How do I know what gender and sexual orientation I am?

I can’t dissect these intuitive processes the way I can pick apart a theological argument. But I can’t retrain my traumatized nervous system through political analysis alone. My head’s gone as far as it can go. Mistrust, fear, and alienation can only be overcome through openness to receiving the life force wherever it manifests.

My intuition knows that quickening feeling when a new line of inquiry makes me feel vital, curious, clear-headed, creative, and pleasurable. That’s the thread I follow through the labyrinth in my creative writing. Now I’m taking baby steps, with some guilt and anxiety, toward the same non-dogmatic attitude in my religious life.

Religion was where my inner child sought order, stability, clear moral boundaries, and the public accountability created by community norms and rationally defensible creeds. Traditional Christianity appealed to and reinforced my dualistic thinking: faith/superstition, good spirits/evil spirits, magical mystical sacraments/New Age hippie make-believe. At my most conservative, I was afraid to open a box of Women’s Bodies Women’s Wisdom Healing Cards that I received as a gift, because didn’t the Bible forbid divination?

One of the spiritual abuse survivor blogs I follow, Caleigh Royer’s Profligate Truth, this year has chronicled her journey away from Christianity and her process of healing from child abuse while raising her baby son. We have a lot in common. In her most recent post, she disclosed her current intuitive attraction to Tarot. I heard that little “ping” inside myself that tells me when I’m onto a good idea in my writing. I remembered my fascination with Tarot in college before I converted to Christianity. The mysterious symbols and fairy-tale archetypes on the cards had inspired me to write an epic poem based on random (?) cards I drew from my Aquarian deck. (One was Temperance, below.)

My mind instantly threw up a cloud of objections. “You have no reason to believe this is ‘true’. Aren’t you just looking desperately for patterns in random events? That’s not a grown-up thing to do! How can you take seriously a religion without a complex philosophical foundation? Or a coffee hour?”

Look, I don’t know any of that, either. I just feel drawn to Tarot right now as a source of resonant images to spark my creativity and know myself better. As this xoJane article, “Tarot Reading for Skeptics, Cynics, Nonbelievers and Side-eyers”, explains:

Why use tarot cards?

Personally, I use them for focus and meditation. I don’t tell the future, I don’t see other people’s secrets, and I don’t think I’m communicating with the divine. (It’s cool if you do, though — I ain’t judging.) I find the archetypes and stories in tarot symbolism to be resonant and meaningful for understanding myself and my life. I do self-directed readings to give myself points to think about, or to reframe my perspective. For me it’s really just a self-help practice with pretty props.

Do you “believe” in tarot as a supernatural/occult/magic thing?

Personally, no. And in general I believe any sort of faith associated with tarot use is fully optional. People will probably argue with me on this point — as I would have done when I considered tarot reading a spiritual activity — but no, you can be a flat-out atheist and still get use out of tarot cards, if you want.

Rational (if not fully scientific) efforts at explaining the efficacy of tarot for some folks often use what Carl Jung — founder of analytical psychology — termed the “collective unconscious.” Jung believed that this was a separate psychological aspect from our personal unconscious, and was not dictated by our individual experience but by the breadth of human existence, taking shape as our shared ability to recognize a series of basic universal forms that he called archetypes.

Examples of archetypes are pretty familiar to human storytelling, and include our ideas of the hero, the mother, the self, the wise old person, the trickster, and so on — most of these broad archetypes can be found in myths and folklore throughout time and across diverse cultures. Thus, Jung argued that this collective unconscious passes from one generation to the next as an inherited understanding shared by all humans.

Tarot cards — especially those who take their symbolism from the Rider-Waite standard — often employ these so-called universal archetypes. Even if you think Jung is full of shit, much of the symbolism used, especially in more modern decks, comes from human experiences many of us can relate to on some level — heartbreak, joy, falling in love, achieving a goal, a fleeting moment of feeling in tune with the world around us — and so with practice they will speak to you in their own ways.

On Ash Wednesday, on my way to my Internal Landscapes lesson, I passed the Church of the Holy Innocents to check on service times. I sometimes attended Mass there in 2000-02 when I worked in an office nearby and needed a mid-week spiritual recharge. It’s everything a small Catholic church in Manhattan should be: shadowy, smoky, crammed with aging plaster statues and paintings of beautiful agonized saints. In true on-the-go New York fashion, they were offering round-the-clock imposition of ashes from 7 AM-7 PM in the basement chapel. Next to the prayer station was a makeshift gift shop with elderly ladies selling saints’ cards, rosaries, beaded bracelets with saints’ pictures, and devotional booklets.

I used to have a childlike faith in such items. I attributed protection to the Jesus lucky charm, rather than the relationship with God that it represented. And by “used to” I mean until 2009 or thereabouts, when traumatic aspects of the adoption process made me realize I was a child abuse survivor. I became cynical and bitter about looking for rescuers outside myself. I wanted to stop clinging to the illusion of control over external circumstances, and instead grow stronger by loving myself and seeing my situation clearly. Rituals and saints seemed like painful reminders of a helpless child’s imaginary friends.

I’m just beginning a new stage of my healing journey, focusing on body-mind integration and openness to God’s presence. With that orientation, and with John Ollom’s insights about the undivided energy of Eros, my view of religious tchotchkes shifted once more.

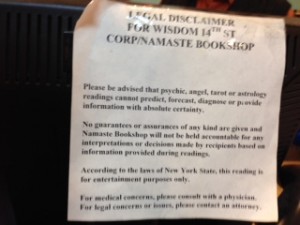

After my movement lesson on Wednesday, I took the subway down to Namaste Bookshop to buy a Tarot deck as a souvenir of my New York spiritual pilgrimage. The colorful, welcoming store is packed with books and trinkets reflecting just about every New Age, Eastern, and indigenous tradition you can imagine: Goddess cards, angel cards, wolf spirit totems, Ganesh statues, charm bracelet Buddha heads… Since New Yorkers are never too spiritual to call a lawyer, the cash register also sports this lovely disclaimer about the store’s fortune-telling services:

The religious smorgasbord before me brought out my cynical side at first. When all traditions are presented as equally valid and on sale for $14.99, doesn’t that encourage shallowness, cultural appropriation, or a superstitious dependence on any barely-understood totem that gives you a good feeling that day?

But that objection fell away when I understood that the whole world is already sacred, already “charged with the grandeur of God” that shines out from every material object, waiting for us to notice it. The Spirit is not something separate from daily life, which we must bring in by choosing the right set of rosary beads or tarot cards. Any of these objects could work as a point of connection to the life force, just as any of them could become an idol if used in the wrong frame of mind.

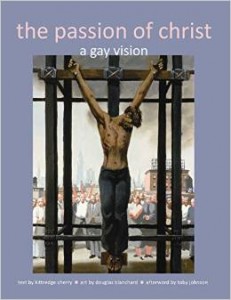

I’m not saying “all religions are the same”. Beliefs have consequences: some are conducive to justice and love, others hurtful and misleading. Symbols, on the other hand, exceed the boundaries of any single interpretation. Jesus has been claimed for many contradictory agendas. Does the Cross represent God’s solidarity with abuse survivors, or does it reinforce abuse by romanticizing the suffering of innocents? Does the Incarnation represent the complete reconciliation of human and divine, or does it imply that human beings other than Jesus lack the divine spark? My heart’s attraction to the Cross transcends arguments.

Don’t ask me where I’m going, but I’m having a good time.