December is the season of Advent in the Christian liturgical calendar, a four-week season of spiritual preparation for Christmas, as well as anticipation of the Second Coming and Last Judgment. (You won’t hear any songs about that in the mall–at least not in the liberal Northeast.) In Protestant churches, the lead-up to Christmas is also the only time of year when an important holy woman, the Virgin Mary, is depicted in our religious scenes or named in our songs. Even then, as I discovered while researching my small-group curriculum on sacred music, there are no hymns with Mary as the main character in the “Christmas” section of the Episcopal Church’s 1982 Hymnal.

At her blog Love Joy Feminism, evangelical-turned-atheist Libby Anne marked the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses by considering “What Women Lost in the Protestant Reformation”. Libby Anne passed through Catholicism on her journey out of Christianity. Although Catholic doctrine on women and gender is still problematic by modern liberal standards, the historic Church offered more religious role models and life paths for women than did its Protestant competitors:

During the middle ages, numerous female mystics and theologians made an impactin religious faith and practice. Julian of Norwich, an anchoress, is an excellent example, but she is not alone. Hildegard of Bingen, an abbess, wrote theology. Bridget of Sweden wrote an extremely successful book on her revelations and founded a religious order. Mechthild of Magdeburg, Gertrud the Great, and many others wrote books and outlined visions. Catherine of Genoa changed the Catholic conception of purgatory.

With the coming of the Protestant Reformation, religious vocations that had offered women the opportunity to study, contemplate, and write disappeared, replaced by the expectation that all women marry and spend their time in childbearing. The Protestant Reformation circumscribed women’s options, leaving them with just one—submission to an individual man who would be their lord and master.

No longer could a woman become an abbess, gaining some authority over others in her sphere. No longer could a woman eschew marriage and choose instead devotion to religion and learning. Certainly, convents were not perfect. In some cases wealthy women were sent away to take religious orders if her parents did not have enough for a dowry, whether that was their choice or not. The availability of options did not mean that choices were not circumscribed. They were. But with the elimination of options, their choices became only more circumscribed…

…The Protestant Reformation changed the very nature of women’s space. It changed the terrain on which women negotiated their role in society. No longer could a woman go to the pope and petition to create her own religious order. No longer could a woman opt to spend her life in contemplation and study rather than domestic labor. No longer could a woman live in a space dominated by other women, rather than in a domestic household in obedience to a father or husband. To be sure, the options women had were never perfect—but they were options…

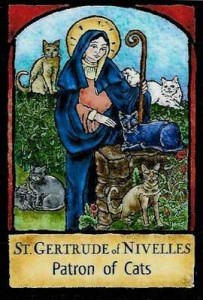

…There is something else women lost to the Protestant Reformation, too—the Virgin Mary. Under the Reformation, religion became much more masculine. Gone was Mary, the Mother of God, and gone were the female saints, whom women had related to, asked favors of, and drawn strength from for centuries. Compare the stained glass windows and images in a Catholic church with those in an old-style Protestant church and you’ll see what I mean. We talk about representation. Mary wasn’t perfect, but she provided that.

For me, the Virgin Mary, like the Cross, is a potent double-edged symbol. It’s all a matter of emphasis. One can critique the sex-shaming involved in equating virginity with moral purity, and the restriction of women to the domestic sphere. However, this is not a flaw in Mary, as much as a side effect of patriarchal tokenism, which puts too much pressure on a limited number of female role models to be all things to all people. Looking at Mary in a positive light, she can represent women’s creative power, independent from men and heterosexual reproduction. Like Jesus, this teenage unwed mother voluntarity took on social stigma to follow her own perception of God’s call.

I relate fondly to Mary as a fellow human being, a nurturing figure in my spiritual pantheon. A mother goddess, on the other hand, triggers me severely, with its implication of a perpetual power imbalance and infantilization of her devotees. At the social justice blog The Establishment, this 2016 article by Amelia Quint explores “How Wiccan ‘Mother Goddess’ Worship Disempowers Women”. Quint, a former Catholic, shares that her decision to remain childless made her feel excluded from the traditional Wiccan archetype of Maiden-Mother-Crone.

The prominence of the Mother Goddess archetype in Wicca is not to be understated; in fact, she seems at times to be an intentional foil to the Father God of Christianity…Though many maintained that this motherhood could be symbolic, of creative works or businesses or your own life, I still couldn’t understand why the spiritual equivalent of the prime of my life had to be expressed by an experience I’d opted out of…

…The growing popularity of spiritual accoutrements and consciousness on social media invites the question: Is emphasizing motherhood really reclaiming the agency we’ve fought so hard for? Feminists have fought for the right to flourish outside the home, yet feminist spirituality in many ways returns them to that sphere. The mystique of alternative spirituality is alluring, but as more women embrace Goddess-centered forms of worship, it’s tough to reconcile the fact that many of these practices emphasize the divinity of masculine and feminine archetypes, keeping traditional gender roles intact.

Quint cites some modern practitioners who are working on making the tradition more inclusive, such as Lasara Firefox Allen’s Jailbreaking the Goddess, which imagines a fivefold Goddess archetype based on talents and life stages other than procreation. Quint also consults philosopher and spiritual counselor Briana Saussy, who posits that the common thread of maternal divine figures in world religions is that they help themselves and others heal from great loss:

Isis had to knit her beloved Osiris back together. Demeter had to search the Underworld for her daughter, Persephone, who had been kidnapped and raped. Mary watched Jesus suffer a violent death.

For Saussy, it isn’t the motherhood that takes center stage; it’s the survival of trauma. Unlike generativity or nurturing, losing something we hold dear is an experience that transcends every social construct. A less literal interpretation might have the “mother” be that which puts us back together again. Saussy agrees: “What these various goddesses really tell us is how to move through those losses and see them for what they are.”

Faith-centered trauma healing is the mission of Rebecca Davis’ website Here’s the Joy, a Christian blog that supports survivors of abuse in churches and critiques abuse-enabling theology. For instance, she advises believers to “suffer intelligently”, that is, to beware of martyrdom theology that romanticizes submission to mistreatment:

There is still suffering in the loss of a relationship and recovery from a betrayal, suffering that will remind us to turn our eyes to Jesus Christ for our hope and healing. But this is not the willful suffering of putting oneself under cruelty on purpose, thinking that it will somehow refine you.

There is only one Refiner. It is Jesus Christ. There is only one way to be refined. It is by faith in Him.

Sometimes suffering is completely unavoidable. Sometimes suffering is a path we must go through in order to attain a vital goal. But instead of assuming that all suffering is desirable, we can ask the Holy Spirit to help us discern. Is this suffering completely unavoidable? Is this suffering to be endured for a vital goal?

Or is this a suffering that we can and should escape?

Davis writes that she began to focus her blog on these issues after seeing her church’s failure to help a friend in a domestic abuse situation. I see the femme face of divinity, nurturing and fiercely protective, at work in projects like these.