Do I forgive my abusive mother? No, but I don’t spend any significant time being angry at her either. A dozen years into conscious recovery, my focus in on noticing and extracting what my old psychoanalyst called my mother’s “introjects” and my trauma therapist called “false beliefs”. They feel like psychic shrapnel. They’re leftover bits of programming from things she said and did to me, or from my own survival adaptations to those assaults. They interfere with my ability to accept love, feel safe in my home, and be satisfied that my creative work isn’t futile. The point is that de-worming myself from these mental parasites has very little to do with her as an individual, anymore.

When she dies, I’ll feel sad, but I feel sad anyway. And all of this can coexist with my telling affectionate jokes about her malapropisms (she insisted that “six of one, half a dozen of the other” should be “half a dozen of one or the other”) and remembering her well-stocked bookshelves of Golden Age mysteries and Native American activist memoirs.

I don’t need “revenge” because (through her own choices, and despite many chances to do better) she’s alone and miserable in a nursing home that I will never visit. Nobody really denies what happened to me or how bad it was.

Vindication by events is key here. I don’t need to ruminate on how she tried to sabotage my adoption home study, because I have a kid now and she’s never going to meet him. But I do entertain vengeful impulses toward the social workers who gaslit me into thinking I had a “personality disorder” instead of PTSD, because I have to look at their agency’s shingle on the building at the end of my street. I can’t go to my favorite movie theater without flashbacks of taking compulsory psychological tests in the building next door. There’s no mechanism, except perhaps hexing, to hold them accountable for causing my nervous breakdown.

I slowly dis-identified with Christianity for a lot of reasons I’ve chronicled here. One of them was that it hadn’t prepared me to recognize when I was being abused. Another was Christian communities’ discomfort with family stories that don’t end in reconciliation or forgiveness.

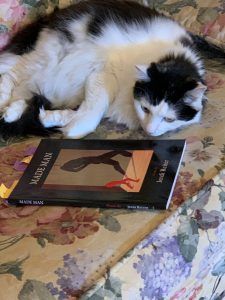

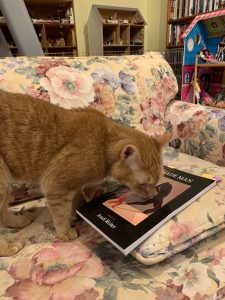

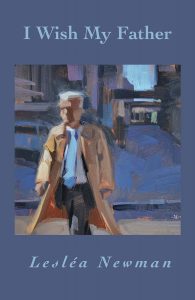

Liberal Catholic journalist Kaya Oakes‘ brand-new book, Not So Sorry: Abusers, False Apologies, and the Limits of Forgiveness (Broadleaf Books, 2024) critiques popular Christian beliefs about the duty to forgive. It’s a really important addition to the conversation because it doesn’t stop at recommendations for better pastoral care. Oakes actually spends most of the book discussing institutional failures such as clergy sexual abuse, colonialism, rape, and abortion access. American Christianity and popular psychology have blended to promote a shallow, individualistic theology of forgiveness that unfairly puts the onus on survivors to be peacemakers in a broken institution. When abusive clergy and community leaders are quietly shuffled around from one institution to another, leaving survivors with a lifetime of damage, “forcing someone to forgive can become a form of spiritual abuse.” (pg.xix)

“[T]he problem with the idea that Jesus was asking people to forgive those who abuse them is that it is not necessarily a correct interpretation of Scripture. Jesus asked us to forgive those who know not what they do. But what do we do about the people who knew exactly what they were doing?” (pg.xvii)

Oakes sees our cultural appetite for revenge-fantasy entertainment as the flip side of sentimental religious redemption stories. Neither track teaches us much about accountability and communal healing, which is what Oakes thinks Jesus really intended. In America, “we fetishize forgiveness to the point of insisting on it–yet in many concrete ways, we are among the least forgiving societies in the world,” Oakes observes (pg.19), pointing to our high incarceration rate, torn social safety net, deadly border-control policies, and insufficient abortion access for rape and incest victims. Preachers love anecdotes about murderers who become Christians and accept God’s forgiveness–but their victims aren’t around to give their opinion. (The book’s epigraph is a quote from Bonhoeffer about cheap grace.) Mass incarceration and the death penalty meanwhile do nothing to heal the community’s wounds.

“Restorative justice and prison abolition movements go even further, encouraging criminals to speak to the families of victims, work on atonement, and bring the community into the process rather than over-relying on often-biased courts. In this scenario, for a person to be forgiven by their community or the families of victims, it’s more than a one-on-one conversation between a person and God.” (pg.28)

Moreover, Oakes emphasizes that this peacemaking process doesn’t require victims to offer a forgiveness that is unhealthy for them or unearned by the perpetrators. The work of death penalty opponent Sister Helen Prejean, for example, is not about mandatory absolution, but about bringing killers back into “reconciliation with themselves” as complete human beings who can face what they did and repent. When Jesus spoke about forgiveness, Oakes notes, he was using a Hebrew word that described people who’d already atoned for their sins and now sought to be brought back into right relationship with God. Notably, Judas tried to do this by giving back the 30 pieces of silver, and was refused. Forgiveness is not infinite nor automatically granted. One can forgive and still refuse further relationship. And one can withhold forgiveness without being vengeful.

Subsequent chapters delve into institutional failures that enabled sexual abuse by leaders in the Catholic Church, the Southern Baptist Convention, and L’Arche, the intentional community where Christians live alongside people with intellectual disabilities. In all these situations, demands for reconciliation put too much responsibility on victims to excuse egregious failures of pastoral care. Oakes is a journalist rather than a theologian but she has certainly begun an important conversation that should be taken up by Christians in other disciplines.