They said it couldn’t be done. They said it shouldn’t be done. They said “hold on, I got my Kindle all sticky…”

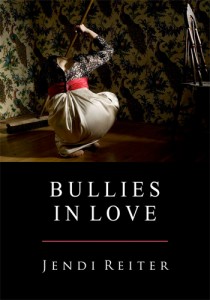

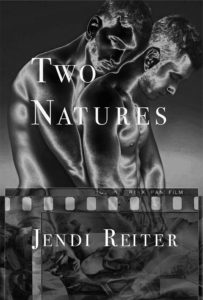

The no-longer-endless novel was published this year by Saddle Road Press and won Best Gay Contemporary General Fiction in the 2016 Rainbow Awards. If you bought it, thank you! Please write an Amazon review. If you haven’t yet, what are you waiting for? The nights are getting colder…

(Book launch party at Bistro Les Gras, Northampton, with the family of choice: Adam, Roberta, Sovereign, & Ellen. I drank a Cosmo on Julian’s behalf.)

In other news, the Young Master is proud to announce that he is nearly 5 and not a baby anymore. He is an expert at identifying construction trucks and different species of trees. In fashion, he enjoys combining homemade paper earrings and Mardi Gras beads with his large collection of robot, truck, and dinosaur shirts. His favorite songs are Major Lazer’s “Bubble Butt” and Justin Timberlake’s “Can’t Stop the Feeling”. He now has the attention span for full-length movies, and likes to role-play scenes from Charlotte’s Web, Finding Nemo and Finding Dory. (I wonder when he will realize how Wilbur the Pig is connected to the pound of salami he eats every week. Ah, lost innocence.) Because of these films, his imaginative play lately includes a lot of baby animals who are sad because they lost their mommies. Is he trying to express something about being adopted? I wish Disney/Pixar didn’t rely on this trope so much. I welcome suggestions of good cartoon films without dead or absent mothers.

After a long and difficult passage, I feel I’m finally settling into a place of peace with my nonbinary spirituality. It’s time to start trusting that Jesus is who I want him to be. Faith means choosing to imagine a divine Friend who lets my attachment and independence ebb and flow, contrary to the template from my childhood and the jealous God that other wounded souls have created in their parents’ image. In my pagan practice, I’ve noticed myself shifting away from “magick” in the sense of trying to make things happen through ritual, and towards using ritual to create a space where I can commune with benevolent spirits. This is not to say that I disbelieve in magick, only that I’m not ready for it. I need a clearer adult perspective to ensure that I’m not returning to childhood strategies of escaping abuse through supernatural fantasy. Or, to put it another way, I need to sit longer with the fear of not getting what I want (hint: book sales) and examine whether I am using this goal to fulfill the wrong needs, before I light candles and bury pins in the ground to feel like I’m achieving something. The Tarot is great for this discernment exercise.

Without further ado, here are the high-and-low-lights of 2016:

Best Poetry Books:

Some amazing books by queer poets of color have been published this year. Joshua Jennifer Espinoza’s i’m alive / it hurts / i love it (Boost House Press) writes with honesty and wit about her life as a transgender woman who manages anxiety and depression. She makes the daily choice to feel everything, though pain coexists with joy. Taxidermy is the organizing metaphor for Rajiv Mohabir’s The Taxidermist’s Cut (Four Way Books): a stripped and reconstituted skin as shapeshifting for survival, as forbidden gay intimacy that always carries the hint of violence, and as inescapable and often misread ethnic identities in a dominant white Christian culture. Mohabir descends from Indian indentured laborers who were transported to British Guyana’s sugar plantations, and grew up in Florida. Another standout debut collection, Donika Kelly’s Bestiary (Graywolf Press), depicts healing from incest as a series of metamorphoses into real and mythical creatures. I’ve currently just started Phillip B. Williams’ Thief in the Interior (Alice James Books), a formally innovative, visceral and intense collection of poems through which the American tradition of violence against black male bodies runs like a blood-red thread.

Best Fiction Books:

Through brilliant use of flashbacks and alternating perspectives, Robert Olen Butler’s A Small Hotel (Grove Press) tells the story of Michael and Kelly Hays, a Southern professional couple who are divorcing after two decades of marriage, though it becomes apparent that they are both still painfully in love with each other. As soon as the reader starts to side with one character, a new twist reveals the other character’s vulnerability and the dysfunctional family pattern that he or she is struggling to break. The novel winds toward a suspenseful climax as we wait to discover whether they will tell each other the truth before it’s too late.

It wouldn’t be a Reiter’s Block Year in Review without Cthulhu! Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country (Harper) is a suspenseful and satirical novel-in-stories about an African-American family in 1950s Chicago who tangle with a cabal of upper-class white occultists. Each chapter cleverly inverts the xenophobic tropes of one of H.P. Lovecraft’s classic horror stories, with the implication that the heartless and greedy cosmic forces of the Cthulhu Mythos are more a self-portrait of Jim Crow’s America than an enemy from beyond the stars.

Best Nonfiction Books:

New York Times op-ed columnist Charles M. Blow’s gorgeously written and introspective memoir, Fire Shut Up in My Bones (Mariner Books), is a case study in overcoming patriarchy and healing from abuse. Brought up in rural Louisiana by a devoted but stern and overworked single mother and their extended family, young Charles yearned for more tenderness and attention than a boy was supposed to need. An older male cousin preyed on his isolation, giving him a new secret to add to his fears of being not-quite-straight in a culture where this was taboo. Channeling his need for connection into school achievement and community leadership, Blow found himself on both the giving and the receiving end of violent hyper-masculinity as a fraternity brother. In the end, he recognized that self-acceptance, not repression, was the best way to become an honorable man. Blow writes like a poet, in witty, image-rich, sensitive lines that flow like a mighty river.

Rev. Elizabeth M. Edman’s Queer Virtue: What LGBTQ People Know About Life and Love and How It Can Revitalize Christianity (Beacon Press) proposes that Christianity and queerness have a common interest in rupturing false binaries that create injustice and estrangement. Read my review on this blog.

Queering Sexual Violence (Riverdale Avenue Books), edited by Jennifer Patterson, is a must-read for social service providers, activists, policymakers, and anyone who studies child abuse and intimate partner violence. The book fills a gap in the common understanding of abuse as something that men do to women and children, and as a social problem best solved through legislation and policing. This familiar picture excludes survivors for whom the carceral state does not routinely offer justice: people of color, the disabled and neurodiverse, and of course the many LGBTQ people who hesitate to out themselves to the police and the courts, fearing that their victimization will only be compounded. Read my review on this blog.

Favorite Posts on the Block:

Tootle and his classmates at the Lower Trainswitch School for Locomotives are cuddly, expressive precursors of the colder computer-generated animation of Thomas the Tank Engine. Scuffy conveys a world of emotion with just eyes, eyebrows, and the tilt of his smokestack. These books are selling nostalgia for an era when America was an industrial powerhouse and no one had heard of global warming or acid rain. However, both tales hammer home a repressive message about staying in your assigned social role and doing what you’re told.

I like the word “bigender” even though my eyes keep reading it as “big gender”. Or maybe that’s why. I have BIG gender. Too much to pick only one.

Who has watched over me during this arduous journey of self-discovery and activism? Where did I get my faith to persevere in the face of spiritual abuse and mental health struggles? I know that I have been protected, by someone I still call “the Holy Spirit” even though most Christian language doesn’t fit me anymore. Someone up there implanted compassion, hope, truth-seeking, and determination in my heart. Someone strengthened me to be true to myself when people I loved couldn’t accept who I’d become. So… thank you, Holy Spirit.

This morning in the bluest of blue states, I took courage from the survival of queer, Jewish, and African-American people through hundreds of years of oppression. I remembered growing up in the 1980s with the constant fear that President Reagan would push the red button and destroy the planet in a nuclear war. I was inspired by the memoirs I am reading this winter for the Winning Writers self-published book contest, about Jews who escaped Nazi Germany and African-Americans who migrated north in the Jim Crow era to seek equal opportunity. And I re-committed myself to upholding the humanity of all people through my work as a writer and publisher.

Book Notes: Gay Theology Without Apology

Comstock argues that any theology based on appeals to authority–even the authority of Jesus–still has more of Caesar in it than Christ. As Audre Lorde said, the master’s tools cannot dismantle the master’s house. The Jesus way is more radical. He called his disciples friends, not servants who obey without knowing why (John 15:15).

Rest in peace, Prince. May we all purify ourselves in the waters of Lake Minnetonka.