My imaginary friends and I have had an eventful year. Some friendships were strained, many others proved more of a blessing than I’d ever imagined. Novel chapters got written, some published, and poetry did even better. My husband and I visited Chicago (AWP), New York City (friends, family and shopping), West Palm Beach (gay rights conference), and three agricultural fairs (we like cheese). My politics moved further to the left, dragging my theology along. Or was it the other way around?

Thanks for visiting Reiter’s Block. I look forward to continuing our conversation in 2010. And now, the clips episode.

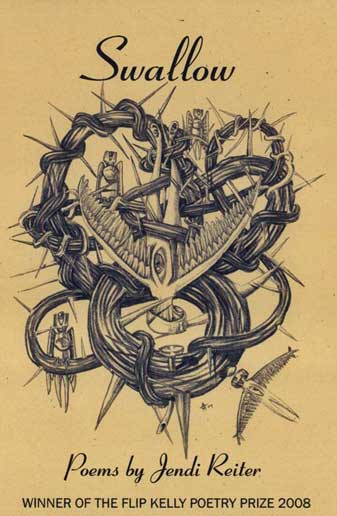

Biggest Accomplishment

SWALLOW. SWALLOW SWALLOW SWALLOW. Buy it now and the scary birdies won’t getcha.

Biggest Disappointment

You know who you are.

Guilty Pleasure

Facebook. Okay, so that’s tangentially related to my writing career. But…

Even Guiltier Pleasure

Farmville on Facebook. This game has no productive value whatsoever. The most I can say is that it’s easier on my wrist than computer solitaire.

Best Books Read in 2009

*Alex Haley, Roots

I thought I understood the story of slavery in this country, but I didn’t feel it in my heart till I read this saga of seven generations of an African-American family, beginning with Haley’s Gambian ancestor who was kidnapped and sold into slavery in the 18th century. Haley’s fictionalized re-creation of their lives is rich with drama, humor, tragedy, political outrage, and love that defies the odds.

*Cheryl Diamond, Model

There’s more to this teen memoir than meets the eye. Beautiful, blonde Cheryl has a wise old head on her shoulders, which helps her survive encounters with all sorts of human predators as she tenaciously builds a career as a fashion model in New York City. She’s also a sharp, funny writer. Now, when I feel defeated by life’s setbacks, I often ask myself, “What would Cheryl do?”

*Adrian Desmond & James R. Moore, Darwin’s Sacred Cause

Two leading Darwin scholars wrote this thorough and engaging history of how Charles Darwin’s hatred of slavery impelled him to seek a common origin for the races. The book has a strong narrative line and a detailed analysis of how politics, religion, and science have been entwined at every step in the development of evolutionary theory.

*David G. Myers & Letha Dawson Scanzoni, What God Has Joined Together: The Christian Case for Gay Marriage

A journalist and a sociologist make a concise and persuasive case that marriage is good for everyone; gays are born that way; and the Bible doesn’t have to be interpreted to condemn homosexuality. While their arguments won’t be news to followers of progressive and queer theology, this is the book I recommend first to anti-gay Christians because it’s written by two straight evangelicals.

*Sarah Schulman, Ties That Bind: Familial Homophobia and Its Consequences

Original, hard-hitting new book from longtime AIDS activist and lesbian playwright casts a critical eye on the family dynamics of shunning and devaluing gay members, and how this becomes the template for the same behaviors in the wider society, as well as domestic abuse in gay relationships. Amazon reviewer C. Bard Cole writes, “…a tight and focused master work. Her approach to talking about the painful family dynamics in her own life is unlike anyone else’s, so unlike the calculated confessional approach of memoir and transgressive fiction that I hardly know how to describe it. It’s cool, intellectual, self-controlled — but perhaps like Perseus looking at the Gorgon only as a reflection in his shield.”

Favorite Blog Posts

“Blogging for Truth” Week: Writing the Truths of GLBT Lives

As Pontius Pilate famously asked, “What is truth?” Who gets to tell it, and about whom? The debate between affirming and non-affirming Christians is fundamentally about the relationship of truth to power. For that reason, it should concern all Christians, whether or not they have a personal stake in GLBT rights.

Liberal Autonomy or Christian Liberty

Original sin distinguishes the Christian picture of human nature from the liberal one. Privileging personal experience over text and tradition, a liberal might say “The truth is inside you.” I wouldn’t go that far. As a good postmodernist, I would say “You are inside you.” The right to stay grounded in our own experience should not be conditioned on the impossible burden of always “getting it right”. That’s another form of legalism.

I’m a Barbie Girl, in a Fallen World

When I’m with my Barbies, I can simply enjoy being a girl. I can pretend that I’m working on narrative structure by inventing elaborate storylines for them — TV show producer Barbie, transgender fashion designer Barbie, 12-step rehab Barbie, closeted evangelical gay teen Barbie, Korean radical feminist ex-stripper Barbie, and the rest. But the truth is, I just love clothes.

Happy 2010 from me and my muse…