Ev’ry eye shall now behold him

Those dear tokens of his passion

Still his dazzling body bears

With what rapture, with what rapture, with what rapture,

gaze we on those glorious scars!

Ev’ry eye shall now behold him

Those dear tokens of his passion

Still his dazzling body bears

With what rapture, with what rapture, with what rapture,

gaze we on those glorious scars!

Serving 110% of that futuristic homosexual decadence, baby:

I discovered the late great Nomi via Kristine Langley Mahler’s March Fadness essay on Taco’s cover of “Puttin’ on the Ritz”. Nomi was a gay German countertenor who fused electronica and opera with space-age vaudeville effects. Sadly, he was one of the first known figures from the arts community to die of AIDS, in 1983. Here he is again in one of my favorite Bowie songs, “The Man Who Sold the World”.

This new Gucci ad starring Elliot Page, actress Julia Garner, and rapper ASAP Rocky as a happy throuple dispelled my last doubts about my upcoming top surgery.

LitHub reports on a recent open letter sent to the New York Times by 200+ contributors protesting the newspaper’s anti-transgender bias.

The letter, which presents a damning and deeply disquieting case against the Times‘ coverage, alleges that there has been “over 15,000 words of front-page Times coverage debating the propriety of medical care for trans children published in the last eight months alone.”

It goes on to reference several prominent Times op-eds and investigative features which have “treated gender diversity with an eerily familiar mix of pseudoscience and euphemistic, charged language, while publishing reporting on trans children that omits relevant information about its sources,” and which have actually been cited by Republican lawmakers in their efforts to pass anti-trans legislation.

Signees of the letter include dozens of prominent journalists and regular Times contributors, including Ed Yong, Lucy Sante, Roxane Gay, Rebecca Solnit, Carmen Maria Machado, Alexander Chee, and Jia Tolentino.

Read and sign the letter here, especially if you are a NYT subscriber. The Hill reports that the NYT responded that they “will not tolerate” criticism from their own reporters. Free speech, amirite?

Parapraxis is a high-quality new online journal of essays about psychoanalysis from a leftist social justice perspective. In their first issue, I especially liked McKenzie Wark’s “Dear Cis Analysts: A call for reparations”, which describes the anti-trans assumptions in the field’s foundational theories, and Nathan Rochelle Duford’s “What Can Men Want?” Ever seen those tweets making fun of right-wing masculinity posts: “Fellas, is it gay to eat pussy?” Well, Junior Soprano would say yes, and Duford explains why. In hyper-macho ideology, the need for intimacy is feminizing in itself, regardless of the object’s gender.

When authoritarians admit of desire at all (including the presumably traditional desire for a genital sexual relationship between a man and a woman), they open up the radical possibility of a sexuality that includes potentially anyone and everyone, any and every bodily or psychic satisfaction from pleasure to pain and whatever lies between or outside them. This also breaks open the possibility of new forms of relationality, of intimacy, of friendship—it presents us with potentialities for social relations that are different or other than the regressive traditionalist fantasy that authoritarians hold of a normal family in which all desire can be fulfilled. As a result, fascism requires a set of seemingly confused norms surrounding gendered sexualities that begin to expand to include all elements of life, not just genital sexuality…

…As Lacan puts it, “man’s desire is the desire of the Other.” It isn’t only desire for the other, but desire of what the other desires—when one desires, one desires recognition in and through the other’s desire. From this provocation, we arrive at a doubling of lack and insufficiency. Admitting of desire, to want at all, is also admitting to insufficiency and an insufficiency we will never be capable of fulfilling for ourselves. We can see here the organic connection between the idea that having sex with women is gay and the idea that men should not masturbate. In each case, sexual desire, especially in its fulfillment, demonstrates the absence of completeness and the presence of need. This need for the other (even in fantasy) is a fundamental form of weakness because it’s possible that it won’t be fulfilled, showing the insufficiency of the person in need. In both cases, sleeping with women and masturbating (what you may think of as typical straight-guy activities) are demonstrations of a failure of self-control. This is a true failure for the authoritarian because if we have to desire, at the very least we should be in control of it, rather than guided by it. Each of these seemingly normal activities is actually an admission of failure…

…[F]for the fascist (or protofascist) man, sexuality is experienced more as an attack on sexuality itself rather than an expression of desire. The erotics of authoritarian desire are thus short-circuited, routed instead toward hatred for what is outside, destruction of the body of the other, and brutality toward difference. The rejection of a desire for difference, as a rejection of desire, full stop, can be read through all kinds of authoritarian urges to expel, exclude, or annihilate.

In Columbia’s alumni magazine, meanwhile, journalist Heather Radke explains why Nature likes big butts and cannot lie:

I hadn’t realized that we are the only animals that have butts—that this particular set of muscles is a uniquely human feature. I had always thought of humans as inferior runners and was taught that standing upright and using tools were the keys to human evolution. But Daniel Lieberman, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard and the go-to guy on butts, believes that the unique way that humans run was actually an important factor in our survival. Humans are slower runners than four-legged animals, but thanks to the butt, we have something they do not—endurance. The gluteal muscles are the largest muscle group in the human body, and their strength and positioning are what allowed humans to keep running and chasing prey when other animals had to stop. That endurance gave humans a competitive advantage that became crucial to how we were able to survive and acquire the calories necessary to maintain and develop our brains.

Radke’s cultural history of Sir Mix-A-Lot’s favorite body part, Butts: A Backstory, is available from Simon & Schuster.

This enigmatic character study by The Poet Spiel brings up some questions that are never far from my thoughts. When does ritual become neurosis? Can compulsion ever cross back into something sacred? The observers’ tenderness towards the solitary man in this poem suggests that his strange routines have summoned some blessing after all, though maybe not in a way that he could expect or notice.

interpretive solo

this red-faced man

stoops his shoulders

as if to keep his heart

from view

he dabs his pointing finger

into his wasting cola

then presses it

against the center of his chin

to create

a sticky dimple

then reaches downward

with his tongue to lick it off

methodically

he fishes thru his pockets

for those same old books

of paper matches

and lines them three across and

three down then flips their covers

then repeats the sugar dimple

lick-it-off stoop-his-shoulders

as in a prayer to wendy

his goddess of this hamburger joint

where i find his bicycle

and his helmet chained and locked

every noon tending

to this sacred business of

three cups of ketchup

a double wendy burger phasing cold

no tomato just the bottom bun

wipe his palms on his knees

never let the bun touch the matches

fold them toward him

sequences no one knows

except there is a perfect way

and if he gets it wrong

he puffs his lips his face

turns redder than his ketchup

and his shoulders nearly meet

until the puffing

and the redding disappear

then he returns to the counter

where the cashiers know his name

and they know no tomato

and not to bother

with the top bun

on the double burger

he will leave

to waste

Happy February! Tomorrow is Imbolc, the midpoint between winter and summer. Of Celtic origin, the name means “in the belly of the Mother” because the seeds of spring are germinating in Mother Earth.

At Reiter’s Block, every day is trans awareness day. EA Games came out with an update to The Sims 4 yesterday to make my favorite game even queerer:

Top Surgery Scar

Under the same Body category, all players can find a Body Scars category with an option for Teen and older male Sims (masculine or feminine frame) to add a Top Surgery Scar to their Sims.

Binders and Shapewear

With this update, players can find two new assets in Create a Sim. Under the Tanks, in the Tops category, you will find a Binder top asset for your Teen and older Sims. In the Underwear category for Bottoms, there is a new shapewear asset for your Sims as well!

They’ve also added hearing aids and glucose monitors so you can create realistic characters with disabilities.

At Medium, Jude Doyle surveys transmasculine “Patron Saints”, from medieval monks assigned female at birth, to Pauli Murray, “the first Black person assigned female to be ordained to the Episcopalian priesthood.” Doyle notes that the cloistered life was far from a perfect refuge for gender outlaws. It’s good to know that people like us existed, and were considered holy, but we shouldn’t romanticize the compromises they had to make.

Escaping into the church was a privilege, and a gendered privilege at that; we know of dozens of transmasculine monks, but there are no transfeminine nuns on record. Trans girls who ran away from home, fleeing “bandits” or marriage or parents, did not have this option…

The Catholic Church does not merely enforce archaic gender roles; the Catholic Church substantially created the gender binary as we know it, and exported it around the world, violently suppressing gender diversity in the cultures it colonized. The belief that there are only two genders, and that one is inherently superior to the other, was not “natural,” let alone universal; it was learned at the point of a sword, and the Catholics were holding it.

There was a home for transmasculine people, in medieval Europe, but it was within the very institution that was busy making trans life impossible outside the confines of the monastery. White trans men baked bread and brewed beer and tended sheep on the mountainside, and transfeminine people, Black and brown trans people, indigenous trans people, were killed.

At Salon, feminist writer Amanda Marcotte is following the unfolding story of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’s book bans.

[T]eachers in Manatee County, Florida were told that every book on their shelves was banned until otherwise notified. Failure to lock up all their books until they could be “vetted” by censors, teachers were warned, put them at risk of being prosecuted as felons.

The facts of this situation are straightforward: A Florida law signed by DeSantis requires that every book available to students “must be selected by a school district employee who holds a valid educational media specialist certificate,” in most cases, the school librarian. This may sound reasonable on its surface, but as the situation in Manatee County shows, in reality, it’s about creating a bottleneck preventing books from getting into the hands of students. Even more importantly, it’s about establishing the idea that books are inherently dangerous objects, to the degree that no student can be allowed to handle one without heavy-handed surveillance…

…In Duval [County], a principal warned teachers that allowing students to read books could result in felony prosecution.

Marcotte perfectly sums up the philosophy behind censorship:

Authoritarians hate reading for the same reason they hate sex, or any private behavior that allows people to experience thoughts and feelings outside of the authoritarian’s control. Learning to sit quietly and read by yourself is, for most people, the first step towards being able to sit with your own thoughts.

Go make Ron DeSantis mad! Read Electric Literature, a smart online journal edited by (gasp!) a Black trans woman, the fantastic Denne Michele Norris. Some pieces I’ve enjoyed recently include Benjamin Schaefer’s essay “We Need to Talk About Professional Jealousy” and [sarah] Cavar’s poem “My Autism Has a Mighty Appetite”.

In the December 2022 issue of The Baffler, Kristin Martin offers an unsettling exposé of Christian foster care influencers. “Wards of God” describes the latest iteration of the colonialist project to “rescue” children from marginalized communities and use them as props for white evangelism. Two-thirds of kids in foster care are there because social workers found parental “neglect,” a broad term that includes the effects of poverty on families with no abuse history. Instead of helping the whole family achieve stability, the foster care system is geared toward child removal. Foster parents receive payments while birth families have to meet draconian requirements to see their children again, let alone reclaim them. Most children characterized as “orphans” by Christians with a savior complex have living parents who were either struggling to meet their material needs, or deceived about the permanent nature of international adoption. “Scrolling through evangelical foster momfluencer accounts, with their testimonials about how God gets them through the hard seasons of care, and how they get too attached to the children in their homes, you can almost forget about the families on the other side: families that didn’t need to be policed and broken apart in the first place,” Martin concludes.

Hilarious gay advice columnist John Paul Brammer a/k/a Hola Papi! has excellent counsel for a queer writer stuck in a pearl-clutching peer group. Read his latest Substack post, “I Hate My Writing Group”. (Sorry Papi, I don’t know how to add the upside-down exclamation point in this blogging platform.)

Incuriosity is thriving at the moment. People seem incredibly proud of publicly renouncing critical thinking in favor of asserting a frustratingly simplistic “thing good or thing bad” mindset…

Worse yet, we’ve come to think of art—all art—as commercial goods that warrant this calculation of the “Moral Nutrition Facts” to ensure we’re not feeding anything “bad” to our brains. So we arrive at a place where art is constantly screaming its own virtues at us. All the rough edges get sanded away, and the lines between “good person” and “bad person” are boldly drawn with one of those ridiculously large Sharpies in mass-produced, infantilizing literature that reassures us that we are good people for putting it on our shelves.

Archives can be subversive. As DeSantis and his fellow authoritarians know, erasing a people’s history makes them isolated and vulnerable to political elimination. I recently had the privilege of touring the David Ruggles Center, an abolitionist history museum in Florence, MA. Their Black history library is available for on-site use only, since their all-volunteer staff can’t keep up with running a lending library. I was sad that all this knowledge never reaches the average middle school or high school classroom. Heck, I went to expensive private schools and colleges in liberal cities and didn’t learn most of the stuff I’m discovering from The 1619 Project on Hulu.

At Nursing Clio, a blog about social justice issues in gender and medicine, Amanda E. Strauss writes about being the director of a new archive about childhood sexual abuse at Brown University’s John Hay Library. The project was barely underway when COVID lockdown hit, Strauss’s father died, and she recovered her incest memories.

I disclosed my truth – “I am a childhood sexual abuse survivor” – one by one to the colleagues and students working most closely on the collections. I led discussions on ethics and spoke with the voice of a well-trained archivist, a confident leader, and that of a survivor. It was the practice of years that kept me going during these conversations as my vision tunneled and the room began to tilt. As during the early months of COVID, the careful boundaries and personas I created to partition my past from the present and my personal from the professional evaporated, and the ground shifted under my feet. I would later learn the clinical word for this phenomena – integration. I like to think of it as healing.

So apparently M&Ms has retired its spokescandies after FOX News host Tucker Carlson complained they weren’t fuckable enough:

Woke M&M’s have returned. The Green M&M got her boots back, but apparently is now a lesbian maybe? And there’s also a plus-sized, obese Purple M&M…

M&M’s will not be satisfied until every last cartoon character is deeply unappealing and totally androgynous, until the moment you wouldn’t want to have a drink with any one of them. That’s the goal. When you’re totally turned off, we’ve achieved equity. They’ve won.

In the Reiter’s Block household we only eat sugar-free transgender M&M knockoffs.

So I really think it’s time we talk about our corporate mascot kinks. What housewife or latent homosexual hasn’t wanted the Brawny Paper Towel Guy to appear outside their kitchen window? (As of 2017, there’s also the lipstick lesbian version, thanks to Georgia-Pacific’s #StrengthHasNoGender campaign.)

Thirsty holes fan fiction just writes itself, am I right?

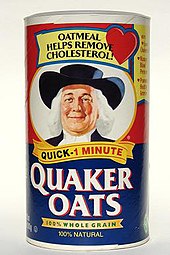

Every morning, like a good autistic, I eat the same thing for breakfast: a two-egg omelet and Quaker Oatmeal with soy milk. I got to talking with my equally filthy-minded family about the important questions: Who is the Quaker Oatmeal man and can he get it?

According to the website Pop Icon, his name is Larry and he was redesigned in 2012 to be slimmer and more youthful than the fellow we remember from our childhood cereal canisters.

While many have thought the Quaker man was designed after William Penn, Quaker has stated he was chosen due to the Quaker faith projecting “the values of honesty, integrity, purity, and strength.”

Looking pretty good for a guy who made his debut in 1877, Larry was America’s first registered trademark for a breakfast cereal (thus saith Wikipedia). In 1965, a new advertising slogan was introduced: “Nothing is better for thee, than me”.

Come to Daddy…

Pop Icon will lead you down the rabbit hole of researching other classic mascots’ names and backstories. For instance, did you know Cap’n Crunch liked to “sail the milk sea” with a mermaid girlfriend?

![]()

“Magnolia Bulkhead”…wasn’t she on RuPaul’s Drag Race?

Another staple of our household diet, 90-second microwaveable rice packets, no longer bear the smiling face of “Uncle Ben” since the 70-year-old brand changed its name to “Ben’s Original” during the anti-racist reckonings of 2020. Aunt Jemima was retired by parent company Quaker Oats in 2021 for the same reason. The brand is now called “Pearl Milling”. The website Organic Authority explains the offensive stereotypes behind these characters:

The use of the term “Aunt” (and, for that matter, the “Uncle” on “Uncle Ben’s,”) wasn’t familial. Rather, it was a term used for elder slaves that often worked in homes instead of the fields. Using the word “aunt” and “uncle” in place of “Mrs.” or “Mr.” lowered their status with their masters.

The Aunt Jemima brand is now mostly known for its syrup, but it started out as a quick-rising flour, mainly used for pancakes and biscuits. Its popularity exploded, and by 1915 it was one of the most well-recognized logos in the country. It even changed trademark laws to help protect its iconic mascot. Early versions of the Aunt Jemima flour packaging included paper doll cutouts for children that showed Jemima and her family barefoot in old, tattered clothing with an option to make them over in nicer outfits as part of the rags to riches story, further elevating the white savior narrative. Their success only came at the hands of the white founder and customers.

“The character of Aunt Jemima is an invitation to white people to indulge in a fantasy of enslaved people — and by extension, all of Black America — as submissive, self-effacing, loyal, pacified and pacifying,” Michael Twitty, culinary historian and author of “The Cooking Gene,” wrote for NBC News. “It positions Black people as boxed in, prepackaged and ready to satisfy; it’s the problem of all consumption, only laced with racial overtones.”

I can’t argue with the need for an update of these problematic logos. But I hope the endgame isn’t to scrub all images of Black characters from advertising. Could the “Ben” on the rice package (currently not depicted at all) be redesigned as a modern role model, like a Black businessman or chef? Is it even possible, though, to create a non-stereotypical product mascot who’s a person of color, in a racist society like ours?

Happy 2023, folks. My resolutions this year are to organize, downsize, and appreciate my resources.

Because even when I was a woman, I didn’t need this many handbags.

R.L. Maizes’ satire piece at Electric Literature, “On the Eighth Day God Attended a Writing Workshop,” imagines giving feedback on Genesis:

Levi, flipping through pages: The beginning was a quite a slog. Does anyone honestly care about the firmament? (Workshop participants shake their heads no.) Maybe just start with the apple incident and give us information about the rest of creation when we need it.

Selena, looking up from her laptop: Is the book supposed to be nonfiction? Because I don’t get how a couple like Adam and Eve who are just starting out can afford to live in Eden when I can’t even make the rent on my Jackson Heights studio.

God: Can I just—

Jason: Sorry, Ya. The Author doesn’t get to talk during the discussion. You’ll have a chance later.

This fantastic erasure-poem from J I Kleinberg in the latest issue of DIAGRAM, “Joining the Academy: A Job-Match Game,” discovers gems in found text. Would you like to attend the “College of better odds” or visit “The Museum of jam”? Perhaps you are qualified to become a “professor of sweaty foot smell” or the “Prefect of Lips”.

Also in DIAGRAM 22.6, this set of illustrations from a 1975 ornithology textbook shows birds multi-tasking by eating a lizard during sex. Their facial expressions suggest they know you’re watching and they enjoy it.

In the Jan/Feb 2023 Harvard Magazine, Nancy Kathryn Walecki profiles happiness researcher Arthur Brooks.

The way Brooks sees it, happiness is a combination of enjoyment, satisfaction, and purpose. The “four pillars” that support that trifecta are family, faith, friends, and work.

“Faith is anything transcendent that helps you escape the boring sitcom that is your life,” he says. It could be a meditation practice, time in nature, religious faith, or even playing music (he recommends fugues by his favorite composer, Bach). Work, on the other hand, is anything that helps a person sustain herself and her family. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a passion, but it should be something that makes a person feel useful in the world…

…Americans have an inalienable right to pursue happiness, Brooks says, but are not always good at the pursuit. Instead of putting their energy toward building their four pillars, they chase the four idols: money, power, pleasure, and the admiration of others. “Mother Nature doesn’t care if you’re happy,” Brooks likes to say. “She cares if you reproduce. So, the things we crave are not always the things that are going to make us happy.”

…Most of Brooks’s [Harvard Business School] students have an incorrect definition of happiness when they start his “Leadership and Happiness” class, he says. They tell him happiness is a feeling. “That’s like saying that Thanksgiving dinner is the smell of your turkey. Happy feelings are evidence of happiness, not the whole thing,” he likes to say.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this December article from PsyPost reports that “People with unhappy childhoods are more likely to exhibit a fear of happiness, study finds”.

Aversion to happiness beliefs were stronger among people who were younger, more lonely, and more perfectionist. They were also more common among people who believed in collective happiness, believed in black magic or karma, and recalled an unhappy childhood.

“The results show that people from collectivistic cultures are more likely to show an aversion to happiness than people from individualistic cultures,” Joshanloo told PsyPost. “At the individual level, perfectionistic tendencies, loneliness, a childhood perceived as unhappy, belief in paranormal phenomena, and holding a collectivistic understanding of happiness are positively associated with aversion to happiness.”

Importantly, reporting an unhappy childhood predicted aversion to happiness even after controlling for current loneliness. As Joshanloo explains, “This suggests that traumatic experiences as a child may have a long-lasting impact on the person’s perception of happiness, independently of the individual’s satisfaction with current relationships in adulthood.”..

…“It is worth noting that happiness can be defined in different ways,” the researcher added. “People are far more likely to be averse to emotional definitions of happiness (based on pleasure, fun, and positive feelings) than virtue-based definitions (based on finding meaning in life and fulfillment).”

For myself, I am noticing a connection between my vast amounts of disorganized possessions and my trauma-habit of believing that fulfillment is exclusively located in the future. When you live in a constant state of emergency, pleasure can seem like an unaffordable luxury in the present. The affirmation “I have enough” risks reconciling you to an untenable situation. The line between equanimity and despair is hard to perceive.

Transgender historian Jules Gill-Peterson’s feature “Doctors Who?” in The Baffler (October 2022) finds present-day political lessons in the hidden history of transitioners who bypassed the medical gatekeepers.

Fifty years ago, a small group of women of color boarded a bus in Southern California bound for Tijuana, Mexico. They may or may not have stuck out in the crowd of Americans who crossed the border daily for the cheaper rates on goods and services. Once in Mexico, these women, who had journeyed all the way from San Francisco, walked into a pharmacy, bought out its entire stock of estrogen, and then carefully hid it inside their luggage. Back home, they made straight for the Tenderloin.

These women were trans—poor, many unhoused, and most sex workers who faced unending street harassment from the police, clients, and other Tenderloin residents. They were also the self-appointed doctors of their community. In hotel rooms, shared apartments, and sometimes the back bathrooms of quiet bars, they resold and administered the estrogen to their friends—other trans women who could pay in cash for injections. At the turn of the 1970s, this group of ad hoc smugglers and lay doctors were part of a vast and informal market in hormones that stretched along most of the West Coast…

…As the liberal principles of bodily autonomy and the right to privacy are eviscerated, the history of DIY transition offers one path out of the quagmire of zero-sum legal arguments and toward what might come after, or in the place of, state-sanctioned care.

Gill-Peterson describes how institutional trans health care “was explicitly designed to limit access to transition” to those patients who would pass as cisgender heterosexuals after treatment.

As feminists and trans activists struggle against the liquidation of the right to privacy, digging into the connections between DIY transition and DIY abortion is instructive. Both reject how medicalization and the state collude to restrict people’s autonomy. And DIY history suggests that one of the core lessons of trans feminism is that you can steal your body back from the state—not to hold it as private property, but because the state power that polices and punishes your body, just like the doctors who execute its arbitrary policies, is fundamentally illegitimate. DIY treats legitimacy as arising from the people whose lives are most affected by resources and care, not from the abstract power of the state or medical gatekeepers.

The trans liberation activists of the 1970s who dreamed of free clinics were part of a political movement that wanted to depathologize transition, so it was no longer treated as a mental illness or a medical condition that required diagnosis and supervision from clinicians with no vested interest in trans people’s happiness…

…DIY has envisioned freedom in starkly different terms. Instead of pathologizing people to grant them access to medical resources, or relying on the state’s flimsy blessing, activists imagined community-run clinics where people to whom transition matters most would support one another and distribute the care they needed. In that framework, both abortion and gender transition would be something like resources for personal and collective autonomy—means to a life characterized by abundance, not dramatized medical procedures contingent on bizarre criteria of deservingness.

A highly eventful year on the Block!

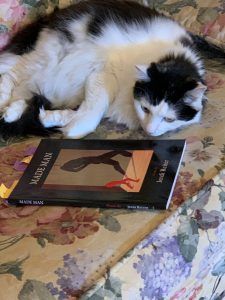

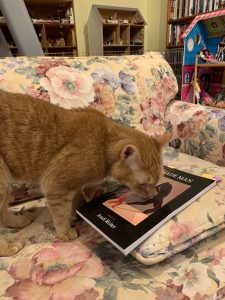

Made My Bones: My third full-length poetry collection, Made Man, was published in March by Little Red Tree, with cover and interior artwork by friend-of-the-Block Tom W. Taylor a/k/a The Poet Spiel. Solstice Lit Mag calls it “a comitragic, day-glo accented, culture-hopping, snort-inducing, gender-interrogating rollercoaster of a ride.” The American Library Association’s Rainbow Round Table says, “A mix of somber moments and charming wit, Reiter’s collection makes space for humor in the maelstrom of navigating gendered experiences.” Made Man was included in Q Spirit’s list of Top LGBTQ Christian Books for 2022 and was the subject of an essay on later-in-life transition by J Brooke at Electric Literature.

Persia Marie says, “The cover feels nice to rub my whiskers against.”

Reading from Made Man at the Brattleboro Literary Festival. Shirt by RSVLTS; suit by Hart Schaffner & Marx; body by Valley Medical Group Endocrinology.

Big Pussy: I turned my home office into a cat AirBnB for my friends’ fur babies when they go on vacation. The shy and regal Persia Marie is the child of artist and writer Jane Morrison. Check out her website for sublime Greek landscapes, caricatures, portraits and more. Ginger rascals Lorca and Rilke belong to author Michael Bondhus and poet/photographer Kevin Hinkle. If you have a reasonably well-behaved cat that you are willing to deliver and pick up in Northampton, get in touch with Uncle Jendi!

Ginny Sack Is Having a 90-Pound Mole Taken Off Her Ass: The impossible has become possible. In March I had a consultation for top surgery. My surgery date is March 23, 2023. As soon as I can lift my arms again, expect this blog to show way too many pictures of my pepperoni nipples.

My Crew: I celebrated my 50th birthday this July by meeting a dear friend in person for the first time. Friend-of-the-Block Richard Jackson, a/k/a the poet “Conway” from my Prison Letters series, visited us with his loving partner Vanity. We were devastated to learn that Van passed away in a motorcycle accident over Thanksgiving weekend.

Nostradamus and Notre Dame: I graduated from Year One of the Temple of Witchcraft Mystery School. Year Two began this past September. My spellcraft is going a lot better, now that I figured out that I was trying to light the incense holder disk instead of the cone.

Waste Management: Why throw anything out when you can glue it together? I made a lot of collage greeting cards this year.

John Ollom and I will be teaching a multimedia workshop at TransHealth Northampton on May 7. We’ll use collage, bodywork, improvised movement, and journaling to guide participants on a journey of gender self-discovery.

You Know Who Had an Arc? Noah: An embarrassment of riches for best books of the year, as I read three novels that would have been #1 on my list, not just for the year, but in general.

Tara Isabella Burton’s sapphic boarding-school novel The World Cannot Give shows idealistic teens getting their crushes all mixed up with their yearnings for transcendence. The author understands, and eventually the protagonist does too, that sincere passions with life-and-death stakes can coexist with a highly performative, aestheticized selfhood. In other words, you might say it’s a Catholic (or Anglican) book, as well as a very queer one, in that ritual and artifice are the container for authenticity rather than its opposite.

Ray Nayler’s The Mountain in the Sea is a hard-science thriller set in a reshaped geopolitical environment, where humankind’s aggressive harvesting of the oceans for protein may have put evolutionary pressure on octopuses to develop a civilization of comparable intelligence as ours. On a deeper level, it’s a dramatization of different philosophies of consciousness, in which the impossibility of truly seeing through another’s eyes becomes an invitation to rekindle empathy and wonder.

GennaRose Nethercott’s Thistlefoot imagines what would happen if Baba Yaga, the witch of Eastern European folklore (and patron saint of this blog), had American Jewish descendants who inherited her chicken-legged hut. The Yaga siblings–a puppeteer with the power to bring objects to life, and a street performer and thief who can uncannily imitate anyone he meets–find themselves charged with the task of laying the ghosts of the pogroms to rest. Don’t miss the chance to see Nethercott perform a puppet show dramatizing sections from her book. Join her mailing list to find out tour dates.

Bro time with Shane at the Big E!

Winning Writers subscriber Duane L. Herrmann emailed me with his latest poetry publications news for our newsletter, and we got to chatting about his Kansas farm and the chores he’s doing to prepare it for wintertime. When he used the phrase “enlarging the meadow,” I suggested it would be a good poem title. Now, here is the poem! Check out more of his work in the anthology Atelier of Healing and the online journals Soul-Lit and I Write Her, among many other venues. His eighth collection, Zephyrs of the Heart, was published this year by Cyberwit.

ENLARGING THE MEADOW

Low bushes invade,

creep into grass,

then additional forbs,

generally called “brush,”

quickly follow.

Their broad leaves,

larger than grass,

encourage tree seeds

to root and sprout,

all causing the edge

of the meadow to move.

After decades it

becomes forest.

To restore supremacy

of grass

all woody plants

must go–back breaking

under hot sun.

In my misspent youth, Princess Diana epitomized fairy-tale feminine perfection. I still have my Charles and Di royal wedding paper dolls. Now, watching Season 5 of “The Crown,” I see the people’s princess as a role model of a different kind, the family member who breaks the code of silence about emotional abuse and neglect. The rules of the system let you get away with almost anything as long as you agree to maintain the façade. Honestly, the Windsors are just the Sopranos with posh accents.

Elizabeth Debicki is doing a great job as 1990s Diana, though the tall actress towers over her co-stars in a way that I don’t remember the real Diana doing. She has the mannerisms spot-on and she can show the princess’s immaturity and self-involvement without making us lose sympathy for her untenable position in the royal family. I wondered why they recast the role, since Emma Corrin was also perfect in Season 4.

Many factors go into casting decisions, of course, but something clicked when I discovered that Corrin recently came out as nonbinary. Maybe the ultra-feminine Diana was too dysphoric a role for them after that. I mean, this Mary Sue article from August 2021 shows them wearing a chest binder! This summer, they became Vogue’s first nonbinary cover model. This BBC article from November quotes them as advocating for an end to gendered categories at film and TV awards shows, following the lead of the Grammys: “It’s difficult for me at the moment trying to justify in my head being non-binary and being nominated in female categories.”

I don’t know about you, but I’m going to be Googling “Emma Corrin top surgery” all through 2023.

On a more sobering note, Politico released a report last month about families fleeing conservative states like Texas and Florida because of bans on transgender health care. The piece profiles a family whose nonbinary teen became suicidal after Texas Gov. Greg Abbott directed child protective services to investigate all parents of medically transitioning kids.

Over the last few years, multiple GOP-controlled state legislatures have advanced bills that would strip access for children and teens to undergo a gender transition. These pieces of legislation have largely been framed by their sponsors as efforts to protect children from “groomers,” pedophiles and doctors intent on doing irreversible harm to their bodies. Though the bills are focused on minors, they have also created fear and uncertainty among trans adults about whether their care, too, could soon be threatened, since many of the sponsors have rejected the idea that people’s gender identity can be anything other than the sex assigned at birth.

Arkansas, Arizona and Alabama have passed laws limiting or outright banning gender-affirming care for minors, while states including Texas and Florida are using executive actions to pursue similar goals. The Arkansas, Texas and Alabama measures have been blocked or partly blocked in court while legal battles continue. Advocates have also vowed to challenge Arizona’s less sweeping law.

Tennessee has a much narrower state law, enacted in 2021, which bars hormonal treatment for “prepubertal minors.” But since young children generally don’t receive that care, experts said, it doesn’t actually have an impact — although some lawmakers have pushed for more comprehensive legislation blocking gender-affirming care…

At least 15 other state legislatures are considering proposals for similar restrictions. At the federal level, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) has introduced the “Protect Children’s Innocence Act” which would ban federal funding for health plans that cover gender-affirming treatment, prohibit U.S. academia from training doctors in how to provide such care and make it a felony for a doctor to give such care to a minor. It has 49 co-sponsors. It has not yet been heard in the House, but that could change as Republicans take control in that chamber next year.

Scaremongering in mainstream media (I’m looking at you, New York Times and The Atlantic) gives the public an inaccurate and overblown idea of the interventions most trans youth actually receive. Doctors interviewed by Politico noted that any kind of gender-affirming surgery is rare for patients under 18, and the most common treatment, puberty blockers, is reversible.

This haunting piece at the flash prose journal fractured lit depicts a different kind of gendered silencing. Tonally reminiscent of Carmen Maria Machado’s feminist horror tales, Grace Elliot’s “In the Closet” is told from the point of view of a mother seeking a private place to scream.

At Narrative Magazine, Emma Brankin’s hard-hitting story “The Red Dress” limns the thought processes of the daughter of a fictionalized Harvey Weinstein figure, as she goes from defending him to recognizing the truth. It’s an excellent dramatization of the selectiveness of memory, not to mention the interpretations we put on it. (You have to create a free account to read this story.)

Perhaps the cephalopods have a creative solution to our domestic woes? CB Anderson’s whimsical essay “On Octopus Sex and the Moon” captures the surreal feeling of late-night web surfing during COVID quarantine.

You link to a science site that confirms one of the male’s arms is like a penis. Called a hectocotylus, it’s capable of erections. Reddit was on the level here.

You learn the hectocotylus can deliver sperm from a distance, which evolved because females tend to kill and eat their partners. One octopus species even has a hectocotylus that functions as a detachable penis, swimming to the female on its own.

Ruminate, a journal of spirituality and literature, sadly closed up shop this autumn. On their website, the speaker in Sarah Damoff’s gorgeous flash fiction “The Naming” juxtaposes thoughts on Adam naming the beasts in Genesis with fragmented memories of a violation that she can’t bring herself to name until the perpetrator is long dead.

Another innovative and darkly funny fiction piece comes to us from DIAGRAM issue 22.5. Channeling the corporate dystopias of George Saunders, James Braun’s “Let Us Have This” depicts absurd and disturbing events at a superstore. The deadpan second-person plural voice, like a Greek chorus, describes a place where workers’ identities become subsumed into (or consumed by) the heart of the Hart-Mart: “we will always be here, even when we are not.”

I was stunned by this graphic memoir in Split Lip Mag by Coyote Shook. “The Young Harris Psalter” reconstructs memories and legends of a forbidding, fascinating great-grandmother who was a rural faith-healer in the Blue Ridge Mountains and died of “brain problems”. After public health clinics came to the region in the 1980s, Shook writes, “She retired unceremoniously and turned her attention to the autoharp, collecting terrifying oddities, and bemoaning the bitterness of her life to anyone who would sit still for it.” A plot worthy of Edward Gorey.

You’re read this far, you can have a little gabagool, as a treat: Saturday Night Live’s “Don Pauly” sketch imagines what would happen if the Jersey mob got “woke”. It’s a scream.

A big Noo Joisey thank-you to Ky Huddleston, editor of Indecent Magazine, for being the first to publish two poems from my Sopranos-themed manuscript in Issue #2 (October 2022). The blurb they wrote for me is better than a plate of gabagool: “Jendi Reiter really shows mastery of ‘wow, there’s a lot going on here,’ in this poem set.” Yeah, people have been saying that about me for a long time.

Please enjoy my poetic tribute to the consigliere, and visit their website for “Ouch, Maenads”, my ode to Ralph Cifaretto.

Silvio Dante Contemplates Puberty Blockers

Sweetheart, you’ve got a very short window.

And don’t you think I know from short?

My suits are like my enemies: I take them out,

a jacket from the boys’ department’s

got no room for a piece.

You can’t spell Bada Bing

without those double curves,

but don’t get hung

up by your own shirt. Time is the great

claw that mothers you back

just when you thought you were out

of the garment bag. I’ve got passages

you wouldn’t believe.

My grandparents from Calabria were spit on

when they came to this country

and sixty years later

they saved it up for me.

My enemies are like my tits:

I genuinely don’t think there’s anything to gain

by keeping them around.