The groundhog may have seen his shadow today, but did he recognize it as himself?

You may have noticed the cute “rat selfies” making the rounds on social media last month. CBC Radio has the backstory about Canadian artist Augustin Lignier, who built a photo booth for his rats Arthur and Augustin to make a point about the addictiveness of social media. The critters were rewarded with food for pressing the camera lever, but soon took pleasure in the action for its own sake.

Arthur and Augustin produced dozens upon dozens of selfies, trying out different angles like real social media pros. But Lignier says they didn’t seem to get any fulfilment from the images themselves.

“I try to show them the images on the screen, so directly after they took the picture, they can see their own selfie,” he said. “But they don’t recognize themselves, you know.”

Philosophers might well debate whether this is a cognitive limitation or a form of enlightenment. The joy is wholly in the act of creation, not the judging and self-promoting ego. For us human artists, that kind of present-moment focus would be a relief, at least some of the time!

I upgraded to the paid subscription to the Straight White American Jesus podcast because I’m obsessed with their lively combo of theological and political analysis of the Christian Right. But their cult-busting mission also extends to the left-wing wellness culture whose paranoid views end up converging with QAnon on topics like vaccines and gender-affirming care. I recommend their July 2023 crossover episode with Conspirituality podcast hosts Julian Walker and Matthew Remski.

I thought of that episode when reading this Alexandra Middleton essay in Electric Literature on Jacqueline Alnes’ memoir The Fruit Cure: The Story of Extreme Wellness Turned Sour. “When so much seems unknowable about the very body you live in, it feels nice to stand on a firm platform made from rights rather than wrongs, even if the very platform itself is a false reality,” Alnes writes about how she fell for extreme diet fads after being struck with a mysterious neurological illness. “Thinking about how many people are failed on a regular basis by U.S. health care systems, it feels totally valid that someone would click on a link to fast for 30 days to cure their diabetes, which I react viscerally to on surface level. But on a human desperation, I want to feel well and these systems are failing me, charging me thousands of dollars a month for very little care, level? 100% get it.”

Ky Schevers writes about a similar example of the horseshoe effect–radical feminists adopting reactionary views on gender–at her trans rights blog Health Liberation Now! Schevers has had an unusual life path, first identifying as a trans man, then becoming a detransition activist, and finally breaking with that community and denouncing their cult-like practices. She now identifies as transmasculine and genderqueer, with she/her pronouns, according to her Wikipedia page. Her longform article “‘A spiritual war in a way’: How Detrans Radical Feminists Influenced WPATH” goes into great detail about how her former community helped introduce stricter gatekeeping into transgender healthcare. Some money quotes if you don’t want to read the whole thing:

Though many [detrans radical feminists] are disillusioned and distrustful towards therapists and other medical professionals and may view the medical system as a whole as part of the larger patriarchy, they’re still very willing to influence it in whatever way they can, especially if they think it will lead to less people transitioning. Many did had negative experiences with medical providers during their transitions but instead of working to improve care they believe that medical transition or even the whole medical system is irredeemable and needs to be shut down and replaced with some kind of alternative healthcare. They’re similar to other people who had negative experiences with healthcare who end up in alt-health cults, who also often end up believing in conspiracy theories and/or reactionary ideologies…

…Gatekeeping only makes sense if you think you can reliably develop a process that will correctly sort out “real” trans people from people confused about their gender. But what if trans people, even those with intense dysphoria, can be psychologically manipulated just as much as any other group of people? Why would trans people be immune to conversion practices or cults?

Following the Oct. 7 Hamas terrorist attack in Israel, there’s been a disturbing amount of groupthink among Jews and those who claim to be our allies. The state of Israel is assumed to represent the values and interests of the Jewish people, and criticism of the former is deemed prejudice toward the latter. I welcomed this contrary perspective from Seth Sanders at Religion Dispatches: “Despite Conflation of Israel with Judaism, Anti-Zionism Is More Kosher Than You Think”.

For 2000 years Jewish prayer has hoped ardently that the Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael) would soon be redeemed by God and led by His Messiah; some even made pilgrimage to visit or dwell with others in the Holy Land. But there is surprisingly little evidence that Jews also always longed for a sovereign State of Israel (Medinat Yisrael) or to be a Middle Eastern political power. It turns out the idea may be shockingly recent, but its novelty is hard to see because we stand on the other side of such a radical transformation in thought. The shift from Holy Land to sovereign secular state has been rendered almost invisible.

…[T]he greatest Jewish philosopher of the Enlightenment, Moses Mendelssohn, wrote in 1770 that “The Talmud forbids us to even think of a return to Palestine by force. Without the miracles and signs mentioned in the Scripture, we must not take the smallest step in the direction of forcing a return and a restoration of our nation.”

It turns out that opposition to a Jewish state isn’t an isolated theological quirk but a central conviction among Jews for most of the history of Rabbinic thought. It’s contained in the Talmud itself, expounded by Rashi (the most important Jewish Bible interpreter, whose interpretation every Jewish Day School student learns first), and detailed by Maimonides, arguably Jewish tradition’s single most influential thinker…

This Messianic view is anchored in the Talmud, which says that the Jewish people must swear to keep faith in God’s plan for the world. The messianic end, when God will redeem all of reality, is a goal so desirable as to be like a bride in waiting for marriage. Thus it is in a mystical commentary on the Song of Songs that Israel is first commanded to swear three oaths: not to “ascend the wall” to where the Messiah (the Bride) waits, not to “rebel against the nations of the world,” and not to “force the End [times].”

Meanwhile, in our nation of so-called Judeo-Christian values, a lot of our food suppliers (including brands with “progressive” vibes like Whole Foods) are taking advantage of modern-day slave labor. AP News reports: “Prisoners in the US are part of a hidden workforce linked to hundreds of popular food brands”.

Intricate, invisible webs, just like this one, link some of the world’s largest food companies and most popular brands to jobs performed by U.S. prisoners nationwide, according to a sweeping two-year AP investigation into prison labor that tied hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of agricultural products to goods sold on the open market.

They are among America’s most vulnerable laborers. If they refuse to work, some can jeopardize their chances of parole or face punishment like being sent to solitary confinement. They also are often excluded from protections guaranteed to almost all other full-time workers, even when they are seriously injured or killed on the job.

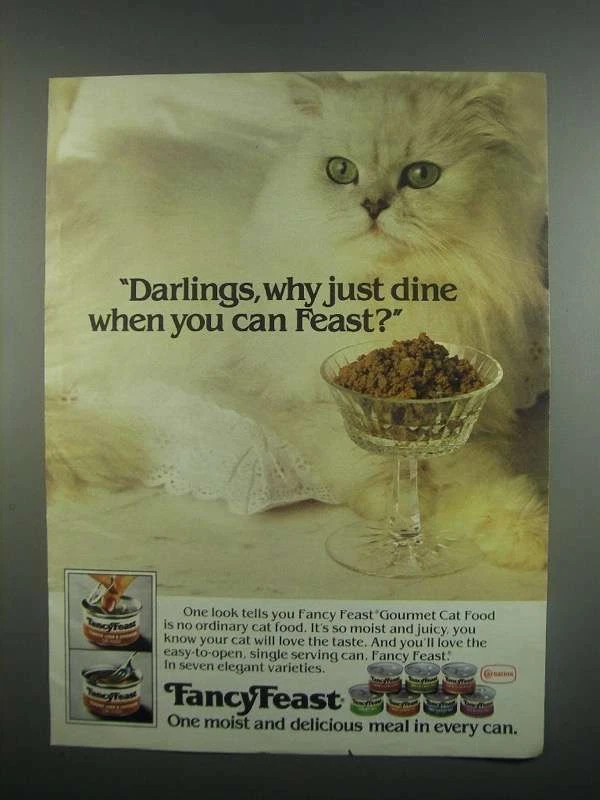

The goods these prisoners produce wind up in the supply chains of a dizzying array of products found in most American kitchens, from Frosted Flakes cereal and Ball Park hot dogs to Gold Medal flour, Coca-Cola and Riceland rice. They are on the shelves of virtually every supermarket in the country, including Kroger, Target, Aldi and Whole Foods. And some goods are exported, including to countries that have had products blocked from entering the U.S. for using forced or prison labor.

Many of the companies buying directly from prisons are violating their own policies against the use of such labor. But it’s completely legal, dating back largely to the need for labor to help rebuild the South’s shattered economy after the Civil War. Enshrined in the Constitution by the 13th Amendment, slavery and involuntary servitude are banned – except as punishment for a crime.

That clause is currently being challenged on the federal level, and efforts to remove similar language from state constitutions are expected to reach the ballot in about a dozen states this year.

Some prisoners work on the same plantation soil where slaves harvested cotton, tobacco and sugarcane more than 150 years ago, with some present-day images looking eerily similar to the past.

Discovered via poet [sarah] Cavar’s newsletter, this essay by Rachael Allen in the journal Too Little/Too Hard challenges the association of “Difficult and Bad” in how we critique writing. Allen talks about dual consciousness as a person of working-class background in literary academia, and argues that ideals of “accessible” writing may underestimate the self-taught intelligence of housecleaners and laborers like her father. When such voices do make it into mainstream publishing, they’re pressured to perform a simplified and traumatic life story that will flatter the benevolence of upper-class readers. “There is a pervading, top-down and patronising mythos of the ‘general public’ or ‘general reader’ – an idea peddled about who can tolerate what under the premise that general audiences aren’t able to manage complicated concepts, formally or linguistically innovative books, or other challenging works, precedents for what is deemed to be accessible set by the middle-class anti-intellectuals that decide it.”

Also on the topic of literary gatekeeping, I recommend this piece in Chicago Review, “Small Press Economies: A Dialogue” by Hilary Plum and Matvei Yankelevich. They call on indie bookstores, review outlets, and distributors to stop disadvantaging small press books in their economic models and attention. I can attest that these barriers are very real.

HP: There’s a failure to understand small press and indie status as a political status and responsibility. For example, look at IndieBound, an organization that represents independent booksellers across the US. They promote a short list of new books every month, selected by indie bookstore staff—a coveted honor that can help launch a book nationally. Understandably, indie bookstores and sites like IndieBound emphasize the importance of independence: you should buy from the brick-and-mortar, rather than from Amazon, and support local community and economy. You should make a little sacrifice on price to protect something you’d miss if it were gone.

But the vast majority of the books IndieBound promotes and celebrates are published by the Big Five. The same is true at too many indie brick-and-mortars. Their uplift of independent, noncorporate business stops at the door—they ask you to buy indie and pay more, but that’s largely not what they do.

MY: So how is that store serving its readers? If you’re a reader and small press books aren’t on the shelf, you’re going to buy what’s on offer. But let’s say you’re into locally and responsibly farmed food and your co-op only carries Cal-Organic, wouldn’t you be concerned?

HP: If you don’t support local farmers, they disappear. People understand that and get why they should buy produce at the farmers market. What’s keeping readers from supporting small presses, and the diverse communities they serve, in similar terms?

MY: It seems to me they can’t see it that way because those presses are hidden from view by structural and economic barriers. On either side of the barriers, institutions, corporations, and small presses themselves often pretend these barriers don’t exist—they’re normalized by the market. Very few literary consumers know that their beloved local indie bookstore is (with very few exceptions) beholden to corporate distributors. Few can imagine what’s missing from those shelves and therefore from their potential reading lives. What’s missing is countless titles from 400 SPD presses, and who knows how many others that don’t have distribution at all.