When visiting a friend in Toronto last month, I had the pleasure of discovering Glad Day Bookshop, the world’s oldest LGBTQ bookstore. One of my purchases was this 1989 essay collection, Christianity, Patriarchy, and Abuse: A Feminist Critique, edited by Joanne Carlson Brown and Carole R. Bohn. There are too few books devoted to reworking Christian theology from a trauma perspective, so I’m always happy to find another. This one shares some of what I perceive to be the limitations of Second Wave feminist theology: binary thinking about gender, and a tendency to imitate the universalizing attitude of their opponents, assigning a single oppressive or liberatory meaning to an image (e.g. God the Father) that is actually experienced in a more complex way by diverse believers. That said, it’s an invigorating and necessary book that doesn’t hesitate to break taboos in order to be firmly on the side of survivors.

Not every essay resonated with me enough to blog about, but I’ll be posting about it now and then, to pull out the insights that meant the most to me. Today I’m looking at the first entry in the book, Joanne Carlson Brown and Rebecca Parker’s “For God So Loved the World?” Parker later expanded this critique of Atonement doctrines into Proverbs of Ashes, the hybrid memoir/theology book she co-wrote with another contributor to this volume, Rita Nakashima Brock. I’ve never gotten around to blog-review Proverbs because the theology is so interwoven with the narrative that it’s hard to summarize, so the executive-summary version here is a real help.

Brown and Parker state the central problem: women have a hard time realizing they are oppressed because they’ve been convinced (by religion, among other forces) that their suffering is justified. “The central image of Christ on the cross as the savior of the world communicates the message that suffering is redemptive. If the best person who ever lived gave his life for others, then, to be of value we should likewise sacrifice ourselves. Any sense that we have a right to care for our own needs is in conflict with being a faithful follower of Jesus.” (pg.2)

As long as Christianity glorifies suffering, Brown and Parker say, women who stay in the church and try to reform it from within are like battered wives who believe they can change their abuser. Whether or not you agree with this strong statement of the case, they correctly, in my view, identify some dangers of the various Atonement doctrines that Christians have accepted.

In classical orthodox theology, the suffering and death of Jesus were required to save us from sin. The three main formulations of how this works are Christus Victor, Penal Satisfaction, and Moral Influence. “[T]hough the way in which suffering gives birth to redemption is diversely understood, every theory of the atonement commends suffering to the disciple” and therefore can keep Christians trapped in abusive situations. (pg.4)

The Christus Victor theory sees the Crucifixion as a supernatural confrontation between God and the forces of evil. In the Resurrection, God reveals that the power of love and goodness is stronger than that of sin and death. This is my own devotional approach to Jesus and the Cross. As I understand it, Jesus’ martyrdom was unique to his role as a divine being, not something we are supposed to emulate. Brown and Parker don’t give this theory the complex treatment it deserves, even in a short essay. They do make the valid point that in preaching and writing about Christus Victor, the reality of human suffering is often minimized as an illusion or a necessary prelude to a person’s spiritual rebirth.

I think they overstate the case when they say that “victimization never leads to triumph” (pg.7) and we should always refuse or fight instead. This isn’t actually an option for every abuse victim. In our haste to build a movement, let’s not set up a hierarchy of “good survivor” behaviors. Also, sometimes refusing suffering in the short-term means enabling it in the long-term, e.g. by not setting boundaries in a relationship before it reaches a tipping point of dysfunction. I don’t believe that submitting to suffering is a virtue in itself, but a mystical sense of oneness with Christus Victor helps me endure the suffering that is a by-product of my choice to resist abusive people and systems.

Penal substitution is the Atonement theory you’ll hear in evangelical churches and probably most Catholic ones. Liberal churches don’t talk about it much, but they generally don’t spell out an alternative, so the congregation absorbs it anyway through the hymns and lectionary readings. The average person thinks “Christ died for your sins” is the Gospel, because that’s the number-one point that televangelists and street preachers want to make you believe. Brown and Parker are ready to drive a stake through the heart of penal substitution, and I applaud that.

In brief, substitutionary atonement means: Sin is an offense against God’s goodness, but we are too flawed to be able to repay that debt, so Jesus, who was perfectly good, was the only one who could satisfy it by taking the punishment we deserved. What’s wrong with this picture?

First, it depicts God as a tyrant who is more concerned with offenses to his honor than with reducing the amount of suffering in the world. (We can see from the U.S. prison system that an emphasis on punishment over rehabilitation has made our society more unjust and violent.) The theory reflects medieval, monarchical norms that are not our political ideal today.

Second, purification through blood sacrifice is a concept taken from ritual practices in the ancient Jewish Temple. Is this framework as relevant to us as it was to Jesus’ audience? Brown and Parker additionally argue that it is a patriarchal displacement of the reverence we should have for the truly life-giving blood, which is women’s menstrual blood and birth flow. As an infertile woman in chronic pain from endometriosis, I feel like a second-rate female when I read this argument (talk about spiritualizing away suffering!), but if you have a better relationship with your uterus than I do, it’s worth thinking about. The authors are correct that patriarchal religions have sanctified certain kinds of bloodletting while projecting uncleanness onto the kind associated with women. On the other hand, the ability to participate in the blood/fertility archetype through symbolic means, when you can’t do it literally, can be a liberating way to “queer” fertility and divinely embodied creativity.

Third, Brown and Parker expose the abuse-enabling assumptions behind penal substitution. For me, that’s where this essay really shines. I remember making a journal entry about 6 years ago, when I’d just begun thinking of myself as a survivor: I suddenly realized that the relationship between God, Jesus, and humanity in Martin Luther’s simul justus et peccator doctrine was exactly like being the child of a narcissistic parent. The real me is sinful humanity, unacceptable and in line for punishment if I try to be authentic. Jesus is the false self I project in order to get “love” and be considered good: the perfect, obedient, enmeshed child, of one being with the Father. But this goodness is only imputed to me through a fiction we both collude in. It never feels like real acceptance.

Brown and Parker write:

The imitator of Christ, which every faithful person is exhorted to be, can find herself choosing to endure suffering because she has become convinced that through her pain another whom she loves can escape pain… But this glorification of suffering as salvific…encourages women who are being abused to be more concerned about their victimizer than about themselves. Children who are abused are forced most keenly to face the conflict between the claims of a parent who professes love and the inner self which protests violation. When a theology identifies love with suffering, what resources will its culture offer to such a child? And when parents have an image of a God righteously demanding the total obedience of “his” son–even obedience to death–what will prevent the parent from engaging in divinely sanctioned child abuse? (pgs.8-9)

The third traditional Atonement theory they critique is Moral Influence, first proposed by medieval theologian Peter Abelard as a rebuttal of Anselm’s penal satisfaction model. This is the one I hear most often in liberal sermons. Abelard contended that the obstacle to reconciliation is not God’s wrath but our unwillingness to believe in God’s mercy. Jesus’ willingness to die for us should be conclusive proof that God loves us and deserves our grateful obedience.

On the surface, Moral Influence seems humanistic and empowering, with its promise that our peaceful forbearance in the face of mistreatment can inspire wrongdoers to repent and reform. But this theology can resemble the false beliefs that make us try to salvage harmful relationships: If I never lose my temper… if I love him more unselfishly… if she sees how much she’s hurting me… they’ll stop the abuse. Moral Influence is perpetrator-centric, and it is least likely to work on the worst offenders because they are incapable of empathy or honest self-assessment. Politically, it also implies that marginalized people’s suffering is ours to consume:

Theoretically, the victimization of Jesus should suffice for our moral edification, but, in fact, in human history, races, classes, and women have been victimized while at the same time their victimization has been heralded as a persuasive reason for inherently sinful men to become more righteous. (pg.12)

…In this pattern of relationship, communion is maintained through the threat of death. The actual deaths or violations of women are part of the system just as necessarily as the death of Jesus is part of the system that asks for us to be “morally persuaded” to be faithful to God…

…To glorify victims of terrorization by attributing to them a vulnerability that warrants protection by the stronger is to cloak the violation. Those who seek to protect are guilty. Justice occurs when terrorization stops, not when the condition of the terrorized is lauded as a preventive influence. (pg.13)

Brown and Parker conclude by surveying some contemporary attempts to rescue Atonement theology from its oppressive past. They give qualified support to the Suffering God theory developed by Ronald Goetz, Edgar Brightman, and the process theologians. “God is unfinished. Suffering occurs because of the conflict between what is and what could be within God. Hence, God participates in the suffering of all of the creation, groaning together with the creation in the travail of perfection coming to birth.” (pgs.15-16)

The problem is that solidarity is not necessarily liberation. We’re still left with the question of why Jesus’ death, or anyone else’s, should be effective, especially when the suffering in question is not an “act of God” (disease, natural disasters) but deliberately caused by human beings. Perhaps a partial answer is that God’s willingness to be wounded by empathy is a role model for us to come out of denial and into true relationship (pg.17). Nonetheless, Brown and Parker would prefer an emphasis on choosing the goodness of life, with suffering as a by-product:

Redemption happens when people refuse to relinquish respect and concern for others, when people refuse to relinquish fullness of feeling, when people refuse to give up seeing, experiencing, and being connected and affected by all of life. God must be seen as the one who most fully refuses to relinquish life… The ongoing resurrection within us of a passion for life and the exuberant energy of this passion testifies to God’s spirit alive in our souls. (pg.19)

I think this part of the essay would have been more successful if they’d acknowledged the paradox of suffering: that we need theology both to help us reject and resist unjust suffering, and to help us find meaning and dignity when suffering is unavoidable. Now, how do we discern which situation is which? Abstract, universal theories can’t substitute for our personal intuition and the guidance of our trusted friends and teachers. No theology is abuse-proof.

Since I’m not attached to calling myself Christian anymore, I can say somewhat more objectively that the authors’ redefinition of “Christianity” as a kind of humanism that rejects all of the faith’s core distinctives–Christ’s divine nature, redemption through the Cross, original sin, the need for salvation, and the historical Resurrection–is almost as crazy-making as it was when I aggressively believed in all those doctrines. Just be a vegan, don’t argue with everyone that your mushroom is a steak.

Maybe this doublespeak is an unfortunate side effect of the authors’ determination to stand and fight rather than suffer. I feel it’s kinder and wiser to take the hit, to grieve for my loss of a home in the church, than to turn the church inside-out so it becomes what I need. I can critique the worst of the abuse-enabling doctrines while accepting the fact that the basic orientation of Christianity, even at its most liberal, is more self-denying than I want to be, and therefore not something I can “reform” my way back into. Do it if it works for you. I’ll visit sometimes.

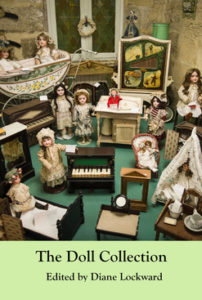

“Not just toys, dolls signify much more than childhood,” writes poet Nicole Cooley in her introduction to The Doll Collection (Terrapin Books, 2016), a rich and complex anthology of doll-themed contemporary poetry edited by Diane Lockward. Dolls are imbued with our powerful, contradictory feelings about gender, race, class, mortality, and innocence. “Symbols of perfection, they both comfort and terrify… They are objects we recall with intense nostalgia but also bodies we dismember and destroy.”

“Not just toys, dolls signify much more than childhood,” writes poet Nicole Cooley in her introduction to The Doll Collection (Terrapin Books, 2016), a rich and complex anthology of doll-themed contemporary poetry edited by Diane Lockward. Dolls are imbued with our powerful, contradictory feelings about gender, race, class, mortality, and innocence. “Symbols of perfection, they both comfort and terrify… They are objects we recall with intense nostalgia but also bodies we dismember and destroy.”