I could depict the timeline of my passions in swag. Pins, keychains, and pendants that proclaimed my shifting special interests, my fervent niche identities, to a world that usually ignored or mocked but occasionally extended the brief warmth of tribal recognition.

And just recently I asked myself, as I picked out more queer nerd tank tops on Redbubble: What have I been driving at, in my lifelong quest for visibility–or more often, my battle against a crushing feeling of erasure? What deeper wounds are reopened when, for example, someone refuses to make waves in a conservative environment by using my nonbinary pronouns–or when I make the same pragmatic choice myself? Why, as an adolescent, did I feel compelled to add to my social awkwardness by literally wearing my heart on my sleeve?

When I was 13, for example, I read British mystery novelist Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time, in which her series detective re-examines the historical evidence for King Richard III’s alleged murder of his young nephews who stood in his path to the throne. The conclusion: He wuz framed, yer Honor. No topic is too obscure to inspire a fan club somewhere in the world, so (impressively in the pre-Internet 1980s) I connected with the Richard III Society in England and bought this lovely pin (figure left) that I wore every day in 9th grade, to the ridicule of my classmates. Yes, my main political activity during the era of AIDS and apartheid divestment was lobbying to reopen a 500-year-old cold case.

In college, I saw the musical “The Phantom of the Opera” and, like many a lonely young woman-adjacent person who liked black capes, fell in love with the title character. This pin (figure right) was my lucky amulet through the ill-advised adventure of law school. Perhaps all that Erik needed was a good real estate lawyer to help him claim title to his underground lair via adverse possession.

My late 20s-early 30s was my peak Christian phase, so I bought keychains like this one saying “YIELD your heart to Jesus” and wore a little diamond cross pendant on the commuter train in hopes that cute guys would strike up a conversation with me about the Trinity. (Reader, they did not. But if you begin an M/M romance that way, I will buy it.)

I don’t have any relevant swag from my “trauma theory explains everything” period, 2008-2015. You mean there’s no market for “emotional incest survivor” keychains? What a surprise!

I rediscovered H.P. Lovecraft around the time that I was becoming disillusioned with Christianity’s abuse apologism. The Elder Gods “religion” is great for mystically-minded cynics because it is simultaneously a genuine apophatic theology and a light-hearted parody of church ritual. We can get our Monty Python kicks from dressing up in tentacled headgear, but we’re also bracing ourselves to confront the cold reality of a non-human-centered cosmos–a bittersweet passage out of father-idealizing religion, into spiritual adulthood.

Which brings us into the wonderful world of queer signifying apparel. In case the boy-band haircut, Eddie Bauer fleece vest, and dozen slightly different blue pin-striped button-down shirts don’t give me away, I have begun collecting pronoun pins, necklaces, and tank tops with Pokemon characters in the colors of the trans flag.

So what does all this mean? Apart from the observation, so routine and widespread as to be cliché (but like many clichés, also true), that Americans are groomed to create brand identities for ourselves through consumption?

A thread that runs throughout my life is the need to struggle against misinterpretation. But it is interwoven with the contradictory thread of ceaselessly seeking an identity that resists definition. Show me what’s the opposite of who I am, and I will try to include it. And then I’ll complain that I’m still being mistaken for another, easier-to-understand category–as though it wasn’t my own choice to become something that has no name.

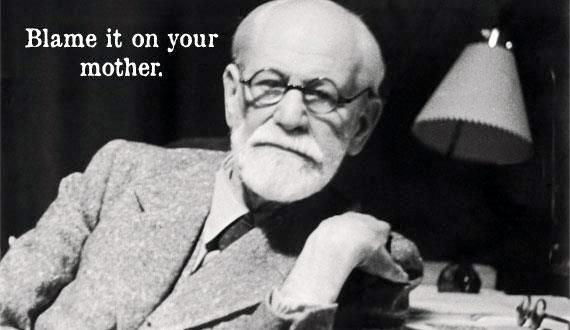

Dr. Freud, up there, would say this is about my engulfment trauma from being raised by a narcissist. Wherever I am, I have to carry some pocket talisman of resistance, an assertion (even if only secretly to myself) that a piece of me remains outside the agenda of the people around me. A crucifix at a radical feminist conference, a Cthulhu necklace in church.

When I was That Kind of Christian, I wore swag to evangelize. I wasn’t concerned with saving people from Hell; I agreed with C.S. Lewis in The Last Battle that all good and loving deeds were counted as worship of the true God, whatever you called your religion. I was desperate to rescue people from shame, perfectionism, and codependence in this life. Because a certain rather idiosyncratic brand of Christianity had done that for me, at that point in time, I hoped it would do the same for everyone. In my non-Christian family and my secular big-city workplaces, and in progressive churches where we glossed over theology instead of wrestling with its historical difficulties, I felt a similar burden of erasure as a conservative Christian in America that I now feel as a genuine sexual minority. Which is why I asked the question that led to this post: is this my psychological pattern, regardless of content?

If so, I am optimistic that the pattern is shifting. At NecronomiCon and Flame Con (the LGBTQ comics convention), I wore my rainbow octopus gear to signal membership in the tribe, to ask for welcome, not to undermine it. And it really worked. I felt energized, relaxed, and appreciated as the current version of my true self–however long a shelf-life it may have.