Who is like the Lord our God, the one who sits enthroned on high?…He settles the childless woman in her home as a happy mother of children. (Psalm 113:5, 9)

Mother’s Day has always been a difficult holiday for me. Unlike Christmas or Thanksgiving, there’s no larger goal to take the focus off one’s personal life and the ways it conforms or fails to conform to a Hallmark card.

Because of her trauma issues, my biological mother never felt sufficiently loved or special. On Mother’s Day, she was especially disappointed and confused by the contrast between how she was supposed to feel and how she actually felt. No matter what we did, it wasn’t enough. Now that she and my other mom are apart, her ex-partner has had space to grow into the mother I need, no longer forced into the shadows. But it’s been a long time coming.

Many infertile and waiting adoptive moms can relate to the loneliness of those years when Mother’s Day came around again and we still didn’t have our child. We belonged to an unseen minority who couldn’t help but recognize the complexity of this thing we call “motherhood”, so oversimplified by the sentimental mainstream. Birthmothers, too, may wonder what this day should mean to them. There are no words for loss in the language of this holiday, just pink flowers and brunch and cards that say “you’re the bestest”.

Last year, on my first Mother’s Day as a mom, I was depressed, and ashamed of it. I loved my one-month-old son. I was so proud to sit in the “parents with small children” pew in church for the first time ever. But the pain of our adoption journey hadn’t healed. I felt pressured by the rhetoric of motherhood to pretend that everything was hearts-and-flowers, that this moment made all the past betrayals worthwhile.

It didn’t help that it coincided with the date when our birthmother’s consent became irrevocable. Now it’s REAL. Help me, mommy! I called her up to give her good wishes and support. Her confidence in me, her comfort with her decision, made me believe I really deserved to celebrate, at last.

Just as I push back against aggressive projections of masculinity onto my 13-month-old (I swear, he comes by that cowboy swagger naturally), I continue to deconstruct the false choices inherent in popular ideas of motherhood. Adulthood and sacrifice versus immaturity and freedom. Being ridiculed for hypervigilance yet blamed for anything that goes wrong with one’s child. Mothering, as opposed to generic “parenting”, is by definition a female activity. And we all know what fun it is to be female in our society. Maybe that’s one reason I was so afraid of it.

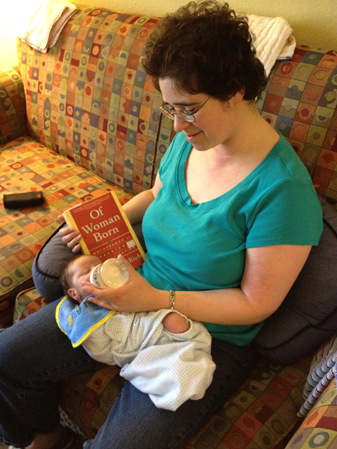

Therefore, mothering, for me, is also an invitation to lean into the political responsibility that goes along with adulthood. This passage from the “Motherhood and Daughterhood” chapter of Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born spoke to me during those early days of transformation into Shane’s Mom:

The “unchilded” woman, if such a term makes any sense, is still affected by centuries-long attitudes–on the part of both women and men–towards the birthing, child-rearing function of women. Any woman who believes that the institution of motherhood has nothing to do with her is closing her eyes to crucial aspects of her situation.

Many of the great mothers have not been biological. The novel Jane Eyre…can be read as a woman-pilgrim’s progres along a path of classic female temptation, in which the motherless Jane time after time finds women who protect, solace, teach, challenge, and nurture her in self-respect. For centuries, daughters have beem strengthened and energized by nonbiological mothers, who have combined a care for the practical values of survival with an incitement toward further horizons, a compassion for vulnerability with an insistence on our buried strengths. It is precisely this that has allowed us to survive…

We are, none of us, “either” mothers or daughters; to our amazement, confusion, and greater complexity, we are both. Women, mothers or not, who feel committed to other women, are increasingly giving each other a quality of caring filled with the diffuse kinds of identification that exist between actual mothers and daughters. Into the mere notion of “mothering” we may carry, as daughters, negative echoes of our own mothers’ martyrdom, the burden of their valiant, necessarily limited efforts on our behalf, the confusion of their double messages. But it is a timidity of the imagination which urges that we can be “daughters”–therefore free spirits–rather than “mothers”–defined as eternal givers. Mothering and nonmothering have been such charged concepts for us, precisely because whichever we did has been turned against us.

To accept and integrate and strengthen both the mother and the daughter in ourselves is no easy matter, because patriarchal attitudes have encouraged us to split, to polarize, these images, and to project all unwanted guilt, anger, shame, power, freedom, onto the “other” woman. But any radical vision of sisterhood demands that we reintegrate them. (pgs. 252-53)

My little pea pod and me in April 2012.

Caretaker of child,

Entwined by strings between souls,

Your smile he calls home.

Best wishes,

Bill Reiter

I must say that I found this essay both informative and disturbing–informative in that it took me into the world of mothers and daughters I had never been in before and disturbing in that I could think of nothing I might be able to do to alleviate similar complexities in the life of any mother or daughter I might know and I have the good fortune to know many of them.

This piece, for all of its clear presentation of the problem, is like nothing I have ever encountered before. Either the mothers and daughters I know do not share these feelings (some probably do) or they don’t feel comfortable in expressing them (that would be my guess).

The sad thing for me is that if an adult woman I know shared thoughts like these with me, whether the woman was related to me or not, I would have no idea what to do or how to react in the adult stage of her life other than to listen without being maudlin.

Maybe I’m wrong in saying, based on my personal experience, that although men have their own problems they don’t seem to leave wounds and later scars as deep as the ones I seem to see here.

Jendi, I do hope some day that you will feel comfortable on Mother’s Day and that you will come to enjoy your son’s cowboy swagger. He can’t help it. And may that swagger later be converted into the great confidence he will need as an adolescent and as an adult to deal successfully with the vagaries and blows of life.

I hope you will have as good a Mother’s Day as your feelings on that day will permit. I can tell you that I can recall a number of Fathers Days in my long life that were moments of reflection not always filled with joy. We do the best we can and hope to leave no wreckage in our wake.

That’s beautiful, thanks.

Donal, thanks for your willingness to learn. You say, “If an adult woman I know shared thoughts like these with me…I would have no idea what to do.” Actually, what you have done in this comment is just right: simply listen with kindness, be present with your confusion and challenging feelings, and not judge or project how the woman *should* feel.

I adore Shane’s confident masculinity. Sorry if that wasn’t clear. I was just saying that it comes naturally to him, it’s not something I impose on him.

Do men have such deep wounds? Probably, but our culture doesn’t give boys enough of a vocabulary to identify their emotions, and they are soon shamed into hiding any vulnerability, even from themselves. I like the books “Real Boys” (William Pollack) and “Raising Cain” (Dan Kindlon & Michael Thompson) which talk about protecting boys’ emotional life while helping them grow into healthy manliness.

On a positive note, I enjoy Father’s Day a whole lot more now…

Jendi, indeed men do have such deep wounds but I think we handle them differently and that does not mean we handle them better–just differently. My wounds came through my Father, a victim of PTSD as the result of being imprisoned at age 16 by the British for running guns for the Irish Republican Army. But I loved my late father deeply because I know that he loved me and tried so very hard to do the right thing.